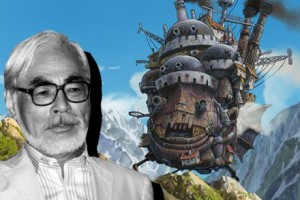

I recently had the great pleasure of seeing Japanese filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki’s 2004 animated feature Howl’s Moving Castle, based on the 1986 young adult fantasy novel by British writer Dianna Wynne Jones. I have long adored the aesthetic shared by the majority of Miyazaki’s Studio Ghibli features, a kind of lush, lyrical, impressionistic steampunk look (the first of his movies I saw was Spirited Away, still one of my favorite films of the 2000s). Howl’s Moving Castle features some of the same types of fantastical airships I had seen in Castle in the Sky and Kiki’s Delivery Service, but what really caught my eye and made me say “Hey! WOW!” were the battleships.

Battleships do not play a major role in Howl’s Moving Castle. However, in Miyazaki’s animated version, the country that protagonists Howl and Sophie live in becomes pulled into a regional war, and several scenes show fleets of battleships setting out for battle or limping back to harbor in severely damaged condition. (Many more of the war scenes involve giant multi-engine bombers and oddball flying machines, since one of the wizard Howl’s guises is that of a giant black bird, and he tries several times to disrupt the air war before his country’s cities are bombed.)

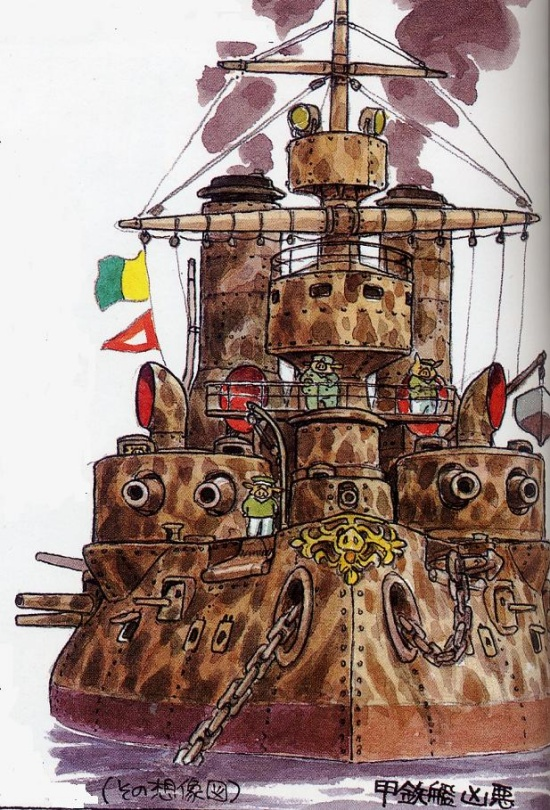

When the battleships appeared, what made me sit up and take notice was the fact that they seemed to be based on French pre-dreadnought battleships of the 1880s and 1890s, the most baroque and distinctive period of French shipbuilding. They also looked to owe a debt to the illustrations of French artist and writer Albert Robida (1848-1926), who, in his prime, competed with Jules Verne for popularity and notoriety as the leading French futurist. Not only Miyazaki’s battleships, but also his airships and even the design of Howl’s Moving Castle itself seemed to pay homage to the distinctive illustrations and fancies of Robida, who is nowadays almost entirely forgotten.

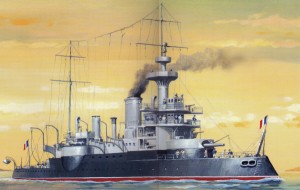

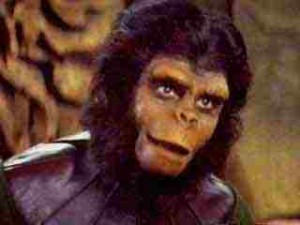

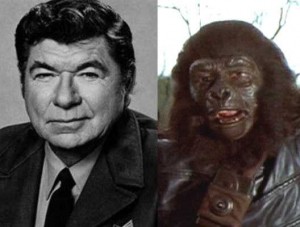

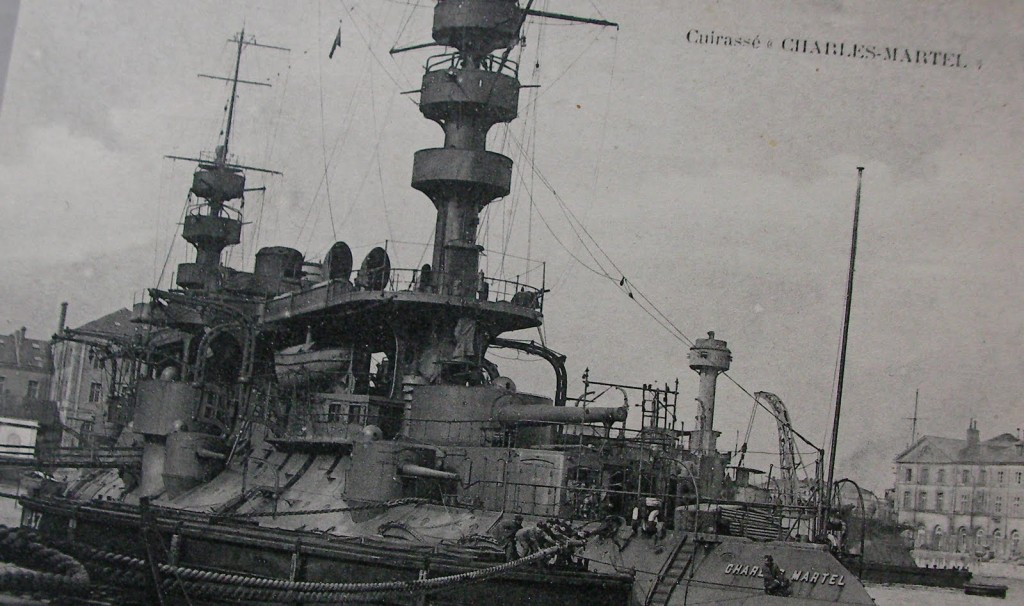

French battleship Charles Martel, commissioned in 1896, epitomized the "French look" for battleships

I confess to being both a science fiction/fantasy geek AND a naval geek. My favorite decades of naval history begin in the 1860s with the introduction of ironclads and extend out to the eve of World War One. The ships constructed between 1860 and 1910 stand as some of the most bizarre (and interesting) ever made, because they were designed and built during years of extremely rapid technological change, change which occurred so quickly that a ship designed, say, in 1880 was considered thoroughly obsolete by the time it was commissioned in 1888. Metallurgy was advancing rapidly in those years, with iron armor (usually backed by teak wood) being replaced by compound armor (steel layered over iron layered over wood), which was in turn replaced by nickel-steel armor (sometimes referred to as Harvey armor), which in turn was made obsolete by Krupp face-hardened steel armor. At the same time armor was rapidly improving, so were the size, range, and accuracy of cannons, not to mention the introduction of new anti-warship weapons, such as submarines, self-propelled torpedoes, and fast torpedo boats.

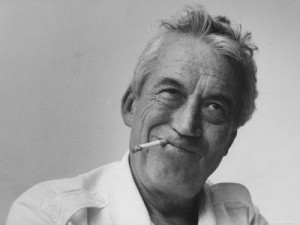

French battleship Massena, commissioned in 1898, showing typical French tumblehome, massive masts, and plethora of long-barreled cannons

The French Navy built the first practical seagoing ironclad, La Glorie, in 1860, forcing their British rivals to launch an even more powerful ironclad, HMS Warrior, later that same year. Early French and British ironclads looked not too much different from the wooden-walled battleships and frigates which had preceded them, having their guns arrayed on the broadsides and mounting vast assortments of sails to back up their steam engines. However, in the 1870s, with the introduction of turrets and barbettes to carry heavy guns and the gradual abandonment of sail, French and British ironclad designs sharply diverged.

The British came to favor turret ships of low freeboard, epitomized by HMS Devastation and HMS Thunderer, the first seagoing ironclads to forego sails altogether. Although they built their oddball battleships, as well (HMS Inflexible and the unlucky HMS Victoria among the weirder), by about 1890 British battleships had come to follow a well-balanced, standard model of moderate freeboard combined with a main armament of four twelve or thirteen inch guns, in one hooded barbette forward and one aft, with secondary guns mounted in sponsons on the broadside.

The French Navy, which viewed the Royal Navy as its primary potential adversary throughout the nineteenth century, went in a different direction with their battleships. In retrospect, it seems as though most French battleships were designed more with threatening, imposing looks in mind than maximum fighting efficiency (Italian naval architects of the period also tended to build visually impressive battleships with tremendous guns, imposing warships which were not very effective or economical; maybe this was a Mediterranean thing?). French designers favored what came to be known as “fierce face.” Most of their battleships combined high freeboard with exaggerated tumblehome (meaning that the ships were much wider at the waterline than at the main deck, with sides that sloped inward and allowed for turrets or barbettes mounted on the broadsides which could fire fore, aft, or to the side). They studded their ships with turrets or barbettes seemingly mounted anywhere they could fit. The cannons were mounted near the fronts of small diameter turrets or barbettes so that the lengths of their barrels would appear dramatically and menacingly elongated. Additionally, French naval designers saddled their ships with massive superstructures and masts of extreme thickness, festooned with large, top-heavy fighting tops mounting small, anti-torpedo boat guns.

This made for battleships which were enormously impressive to look at. I’m sure many non-expert observers, when viewing French and British battleships side by side (say, at a port visit or a Royal Naval Review), must have assumed the French ships would quickly clear the seas of their British counterparts in a fight. The British and French battle fleets never came to blows during the ironclad or pre-dreadnought eras (the only occasion on which French and British battleships would exchange fire occurred much later, during the tragic British attack on the French fleet at Mers-el-Kebir in French Algeria in 1940, after the capitulation of France to Germany, when the British felt they had to prevent the French fleet from being taken over by the Germans). So the issue of which rival battlefleet would prevail in a fight was never conclusively settled. The French fleet was not without its advantages; for several stretches during the late nineteenth century, its armor and cannons were technically superior to those of the British.

However, battleships built by British yards did fight battleships either built by French yards or modeled on French designs at the Battle of Tsushima in 1905. The Russian Baltic Fleet, whose battleships had either been built by French yards or copied from French originals, was annihilated by the Japanese fleet, whose battleships had all been built in British yards and modeled on contemporaneous British designs. Also, on March 18, 1915, when the British and French fleets were allied in their efforts to force the Dardanelles Straits, two British pre-dreadnoughts, HMS Irresistible and HMS Ocean, and one French pre-dreadnought, the Bouvet, were sunk by Turkish mines. The two British battleships remained afloat for several hours, enough time for their crews to be evacuated onto other ships. The Bouvet, however, handicapped by her enormous top-weight and lacking the stability of her British contemporaries, turned turtle in less than three minutes, trapping and drowning 600 of her crew.

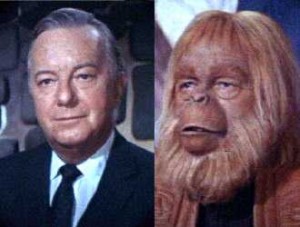

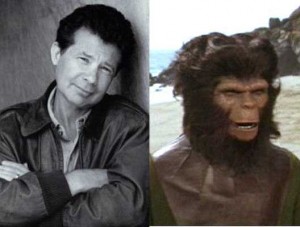

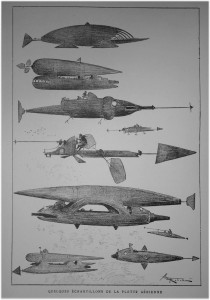

Aside from the inspiration provided by actual French battleships of the late nineteenth century, which Miyazaki has acknowledged, he must also have received significant visual inspiration from Albert Robida. Robida was both a writer and an artist, a sort of proto-graphic novelist of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He was enormously popular between 1880 and World War One, best known for a trio of futuristic illustrated novels, Le Vingtieme Siecle (1883), La Guerre au Vingtieme Siecle (1887), and Le Vingtieme Siecle—La Vie Electrique (1890). Between 1908 and 1910, he provided 520 illustrations, many of them featuring fantastical flying machines and enormous tank-like mobile land fortresses, for the children’s serialized adventure novel La Guerre Infernale, whose installments appeared every Saturday. It described a world war, fought primarily in the air, between Germany and Britain in Europe and the United States and Japan in the Pacific. His illustrations, which influenced dozens of subsequent science fiction and fantasy artists, must be understood as foundational to the steampunk aesthetic.

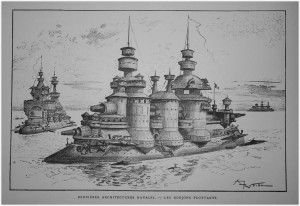

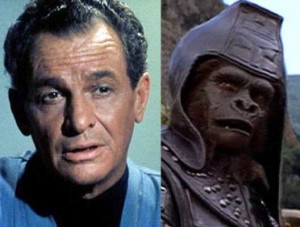

Albert Robida's airships, some of the 520 illustrations he created for the weekly serial "La Guerre Infernale," circa 1908

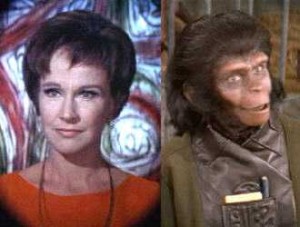

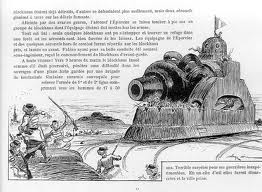

One of Albert Robida's land battleships, looking not too dissimilar from Miyazaki's design for Howl's Moving Castle

**************************************

Many of the appealingly quirky airships which populate the Miyazaki films look very much like Robida’s drawings. Miyazaki’s design of Howl’s Moving Castle looks a lot like a cross between one of Robida’s mobile land fortresses and a French pre-dreadnought such as the Charles Martel. And then there are Miyazaki’s wonderful battleships. In his 1887 novel about the future of warfare, Rodiba included illustrations of ludicrously top-heavy battleships, virtual floating fortresses (which, if built, would neither have floated nor remained upright). Strange as these fanciful warships may seem to modern eyes (and as wonderfully bizarre as the Miyazaki steampunk battleships look), they were simply exaggerations of battleships which were actually built by the French Navy, warships which were among the most visually distinctive ever to sail the seas.