Since I started writing this blog back in July, 2011, my youngest son, Judah, has become a giant monster fanatic (a chip off the old block; I adored all the same stuff at his age). My first “favorite movie” was King Kong Vs. Godzilla, which even at the age of six was a guilty pleasure for me, because I had seen the original King Kong and knew in my heart-of-hearts that Toho’s man in a gorilla suit could not compare to Willis O’Brien’s stop-motion animated Kong. Still, hokey as that guy in a gorilla suit seemed, I couldn’t resist the sheer fun of seeing Japan’s biggest, baddest radioactive dinosaur rumble with King Kong (who gained kind-of-cool electrical powers in the film, a bit of an equalizer to Godzilla’s radioactive breath).

Judah loves all the Godzilla films, from the classics and near-classics (Godzilla, King of the Monsters and Godzilla Vs. the Thing, a.k.a. Godzilla vs. Mothra) to the really “awful” ones (Godzilla’s Revenge, thought by many to be the worst Godzilla film of all, but one which Judah and I both appreciate). He also really digs other giant monster films, favorites including The Deadly Mantis, Tarantula, the Gamera movies of the 1960s and 1970s, and South Korea’s only foray into the genre, Yongary, Monster From the Deep. He has even sat through the Mystery Theater 3000 version of The Giant Gila Monster, although the point of the snarking robots at the bottom of the screen escaped him.

Being five, he will happily watch his favorites over and over again (and I’ll generally comply with his pleas to watch with him, since many of those films never get old for me), but I do my best to “broaden his horizons” and introduce him to films he hasn’t seen before. Netflix is a great help with this parental mission. I saw that Konga, a 1961 collaboration between a British studio, Anglo Amalgamated, and an American studio, American International Pictures, was available for instant streaming. I hadn’t seen Konga since I was a kid, and my memories of the film were somewhat hazy. Still, it had a giant ape in it, rampaging through London, so I figured, what’s not to like?

Plenty, as it turned out. Interestingly, the big ape, Konga, was by far the worst thing about the film. The rest of the movie deserved a better monster. Somewhat unusually for a 1960s giant monster flick, the human performances are quite good, making the very lame FX and ape acting seem all the more limp by comparison. Michael Gough is very memorable as the increasingly deranged Professor Charles Decker, the scientist who mutates a friendly little chimpanzee, Konga, into a massive brute by injecting him with several doses of growth serum. Margo Johns is equally as good as Margaret, Decker’s lab assistant, who, in love with her boss, blackmails him into marrying her by agreeing to go along with his dangerous experiments and utilization of Konga to murder his academic and scientific rivals. The scenes between them crackle with dramatic tension, especially after Barbara learns of Decker’s horndog yearnings for Sandra (Claire Gordon), his young, pretty student.

"If you hadn't injected me with this damn growth formula, I could have stayed a lively little chimp, instead of a comatose giant gorilla!"

Where the film completely falls flat on its face is whenever the ape shows up. Oh, Konga is perfectly acceptable so long as he remains a chimp, portrayed by an actual chimpanzee. But once he is mutated into a full-grown gorilla, he is a black hole on the screen, sucking all of the film’s verisimilitude and audience involvement out and depositing them in some nether region on the far side of the galaxy. Simply put, aside (maybe) from some gorilla portrayals in Republic Pictures or Monogram Studios serials of the 1930s and 1940s, uncredited actor Paul Stockman delivers the most lackadaisical, unconvincing portrayal of a gorilla by a man in a gorilla suit on film. (Stockman has thirteen film and TV credits, none of the others being apes; his only named characters are Inspector Dales in two 1967 episodes of the TV series Adventures of the Seaspray and Steve Parker in Dr. Blood’s Coffin, made the same year as Konga, 1961.) George Barrows rented his gorilla suit to the makers of Konga; the suit had previously appeared in such cinema “classics” as Gorilla at Large and Robot Monster. They would have done as well to stuff a mannequin inside the gorilla suit as put Paul Stockman in there. Stockman makes no effort whatsoever to portray a gorilla. He simply walks around inside the suit, with all the verve and dynamism of a man trying to wipe a wad of chewing gum off the bottom of his shoe onto a patch of grass. Before being turned gigantic by Barbara’s final injection of the growth serum, Konga is directed by Decker to murder three of his rivals. None of the strangulation murders are filmed with any suspense, interesting camera angles, or cinematic energy at all. Stockman as Konga goes through the motions, as though Decker had sent him out to the local pharmacy for some antacid tablets.

Perhaps the film’s biggest surprise is that Konga, who grows to more than a hundred feet tall, doesn’t destroy anything, beyond his initial big growth spurt wherein he shoots through the roof of Decker’s house and stumbles through his greenhouse filled with carnivorous plants. He shambles through the outskirts and then the heart of London and somehow manages to avoid wrecking so much as a single building, smooshing a single civilian (apart from Barbara, whom he tosses to the carnivorous plants, and Decker, whom he flings to the soldiers as though he were discarding a candy wrapper), or trampling a single infantryman. I picture a little two-way radio inside the mask of Stockman’s gorilla suit, with the director constantly warning him, “Mind the budget, you! We can’t afford even a single mangled model car!”

The British Army's marksmanship has sadly declined since the glory days of El Alamein

Accordingly, none of the several dozen extras hired to run away from the giant ape appear to be in much of a hurry or evince much in the way of terror. “Big ponce won’t spend the effort to step on me,” seems to be the general attitude. When the British Army arrives on the scene, they don’t bother moving the crowds back, as though they are unconcerned by the possibility that a few dozen folks might get trampled or have their heads removed by a stray bullet. Speaking of stray bullets, the Nazi Propaganda Ministry of WWII couldn’t have done a more effective job of denigrating the deadliness of Britain’s armed forces than the makers of Konga. As Konga – over a hundred feet tall, mind you, not a small target – poses immobile next to London’s Big Ben, the assembled infantrymen fire several hundred rounds of tracer bullets and rockets at the giant gorilla, from a range of perhaps fifty yards. Every single tracer shell sails harmlessly over the ape’s head or shoulders. Finally, once the filmmakers have apparently grown tired of this incredible display of ineffectuality, and with Stockman in the gorilla suit just standing there and waving an improperly scaled doll of Professor Decker limply through the air, the Army men correct their aim and bring the big gorilla down. The closing shot, the big climax? Through the magic of a blur filter being placed in front of the camera lens, the giant gorilla shrinks back to his original form – which turns out to be a stuffed toy chimp bought from the local toy store. They couldn’t have sedated an actual live monkey for the shot, or at least used a miniature that doesn’t look like it belongs in an infant’s nursery? Supposedly the special effects, among the first giant monster effects to be filmed in color (although Ray Harryhausen had done it to immeasurably greater effect three years earlier with his The 7th Voyage of Sinbad), took eighteen months to complete. What did they do in all that time? Obviously not build miniatures capable of fooling even a three-year-old.

FX horror or horrible FX? Willis O'Brien rolls over in his grave

The most cringe-inducing FX shot comes right after Barbara gives Konga his super-sized injection of growth serum. We get that blur filter again, and Konga shoots up to about twelve feet tall, tall enough to fill much of Decker’s laboratory. He picks up Barbara in his expanded paw – and she is obviously a two-foot-tall doll, of the kind little girls get for Christmas so they can practice styling its hair with miniature plastic brushes. This shot doesn’t last a half-second, which might have ameliorated its awfulness, but a full four or five seconds, which can’t help but make the most casual viewer wonder if the filmmakers were even trying. The worst traveling matte effect would have been an improvement over this travesty – Ed Wood-level filmmaking, but without Ed Wood’s unintentional humor.

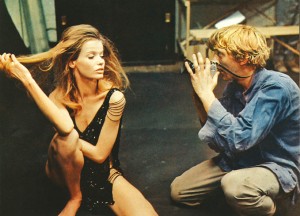

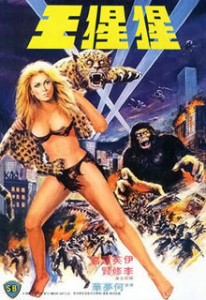

Beauty and the beast, Hong Kong-style

After Konga (thankfully) came to an inglorious end, Netflix, as it is wont to do, suggested a handful of similar films I might enjoy. One of them was a giant ape-man movie I had never heard of, a 1977 Hong Kong production called The Mighty Peking Man. Oh, what fun! I told my son and my wife. This sounds even worse than Konga! We can have a competition to decide the worst giant ape movie of all time! And so we settled in for the second entry in our inadvertent double feature.

I went into The Mighty Peking Man with no preconceptions whatsoever – aside from an expectation that it would be cheesy and generally awful, judging solely from its awkward title and the year of its filming (1977 was simply not a golden year for pop culture). This turned out to be a delightful way to watch this movie, as virtually every five minutes brought a fresh surprise and gasp of appreciation for the momentous heights of fantabulous cheesiness scaled by this film. A little history is in order. The Shaw Brothers Studio in Hong Kong rushed The Mighty Peking Man into production to capitalize on the worldwide giant gorilla craze sparked by Dino De Laurentiis’ 1976 remake of King Kong, which introduced moviegoers to Jessica Lange. The picture, starring Danny Lee as an archeologist/adventurer and blonde bombshell Evelyn Kraft as a female Tarzan named Samantha, wasn’t released in the U.S. market until 1980, under the title Goliathon. However, nineteen years later, in 1999, this obscure film got a second release in the U.S. market, this time under its original name, thanks to the efforts of Quentin Tarantino, who worked with Miramax to rerelease it through his Rolling Thunder Pictures distribution company. At which point it earned a grand total of $17,368.00 in the theaters before being swept away into the Blockbuster bins. I can only assume it has performed somewhat better on home video and cable TV. It certainly deserves to be seen.

Mighty Peking Man, unlike Konga, delivers the goods

From beginning to end, this movie is a hoot to watch, without a dull moment. It displays, in spades, all the cinematic energy which the “horror” scenes of Konga so miserably lack. All the atmospherics work in its favor – its disco-era costuming and soundtrack, as well as its performers’ extroverted acting styles, give it the feel of a Blaxploitation film without Black people (which I’m sure helped to endear it to Quentin Tarantino, that famed fanboy of Blaxploitation). Plus, the filmmakers take the hint of flirtatiousness between Jessica Lange’s Dwan and Rick Baker’s Kong from the hit movie of the prior year and dial it up to eleven, going where no giant ape movie had gone before. Kuang Ni, the scriptwriter, combines the stories of King Kong and Tarzan. Rather than the Great White Hunter/Filmmaker bringing his Blonde Goddess to the Giant Gorilla’s lair, in this instance, a Great Asian Archeologist discovers a Blonde Tarzanna already comfortably ensconced with the giant ape-man in the Himalayan wilderness. Samantha’s parents had perished in a small plane crash near the home of the Mighty Peking Man, and the giant ape-man rescued the tiny child from the wreck and raised her, somehow providing her with a skin-tight animal-skin bikini to wear. Samantha has the ability to communicate with all the large animals in her domain, including leopards and tigers, and she is quite… uh, familiar with the Mighty Peking Man, who she calls Utam. There are a couple of scenes wherein she climbs into Utam’s giant paw and sinuously rubs her pneumatic body up and down his big index finger, as tall as she is, up and down, up and down, those big breasts, barely contained by that animal-skin bikini top, giving Utam a voluptuous manicure… well, I’m sure you get the idea. Sailed right over Judah’s little head, but not my wife’s head. Or my head. Jesus, I need a cold shower after typing that…

Mighty Peking Man's miniatures put those of Konga to shame

Alas, things do not end well for Samantha and her Utam. Archeologist Johnny, doing his best Carl Denham imitation, drags them away from their jungle paradise across the South China Sea so that Utam can be put on public display in Hong Kong. Utam puts up with this in amiable fashion until one of the film’s heavies takes a rude interest in comely Samantha and attempts to rape her – in a hotel room with an open window that just happens to be overlooking the stadium where Utam, in chains, is watching. Utam, to put it mildly, does not take this lying down. Sadamasa Arikawa and Koichi Kawakita, the special effects directors, then put on a hell of a good show. Their miniatures of downtown Hong Kong rival the best 1950s and 1960s work of Toho Studios and are superior to the model work deployed by Daiei Motion Picture Company in their 1960s Gamera movies. The Mighty Peking Man costume is very ugly, reminiscent of the green gargantua costume used in Toho’s 1966 War of the Gargantuas, but the effects men manage to make the mask express a wide range of emotions, and the actor in the suit uses his body language about as effectively and expressively as Haruo Nakajima does as Kong in King Kong Escapes or as Shoichi Hirose does as Kong in King Kong vs. Godzilla — all three giant ape performances being head and shoulders above Paul Stockman’s shameless sleepwalking through Konga. In a revealing parallel with the English-American coproduction, Utam throws his tormentor, Samantha’s would-be rapist, to the ground, just as Konga tosses Decker to the street – only the vastly more energetic Mighty Peking Man then crushes his victim with his giant foot.

Once the closing credits rolled, my supposed contest for the worst giant ape movie of all time ended up as no contest at all. The Hong Kong production is far and away the better movie (Judah and Asher both agreed). Are there any other giant ape movies out there that can rival Konga for wretchedness? I’ve already mentioned the Toho trio of giant ape movies, War of the Gargantuas and the two Kong flicks. I would place them all above Konga due to the quality of their miniature work, the expressive suit performances delivered by their gorilla actors, and their never-boring, endearingly goofy antics and plot turns. I would be tempted to pit Dino De Laurentiss’ King Kong against Konga for the title, since I truly disliked that film, even as a kid, but the high quality of Rick Baker’s performance as Kong uplifts his film and gives it the edge (had De Laurentiss been able to stick with his original plan to solely utilize his life-size King Kong robot for the Kong performance, then we would have a real contest on our hands).

QUEEN KONG, which is also in the running for Least Convincing Portrayal of a Dinosaur on Film

I’ve never seen Queen Kong, a 1976 British comedy which got embroiled in a lawsuit with Dino De Laurentiss and never received a general theatrical release, appearing only in limited release in Germany and Italy. Apparently the film has a cult following in Japan, where it has received entirely new Japanese dialogue, done in the spirit of Woody Allen’s What’s Up, Tiger Lilly?. Sadly, neither version of Queen Kong is available on Netflix. The photos and screen grabs I’ve been able to view online look truly dreadful, so this one might be credible competition for Konga.

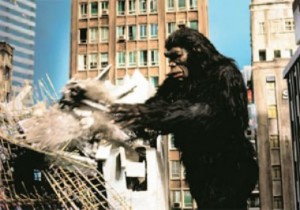

A*P*E, South Korea's entry in the Worst Giant Ape Movie of All Time competition

I also hear that a South Korean production, A*P*E (1976), made, like The Mighty Peking Man, to gobble up some of the box office crumbs left over from the De Laurentiss King Kong, is epically bad. Judge for yourself from the pair of “special” FX photos I’ve so kindly provided.

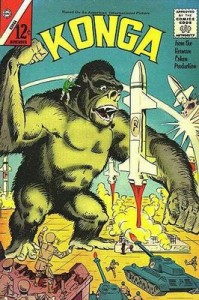

An adaptation much superior to the original

Konga did not sleepwalk in vain, however. This wretched film spawned a far superior offspring in a different medium – Charlton Comics’ 1960-66 comic book series Konga, illustrated by Steve Ditko, the co-creator of Spider-Man. In Konga, Ditko found a character perfectly suited to his unique style of illustration (I would argue that Konga is a better fit for Ditko’s style than even Spider-Man). He took a character virtually devoid of expressive qualities (see my comments above concerning Paul Stockman’s “performance” as Konga) and made him, by turns, whimsical, affectionate, lovelorn, lonely, playful, affronted, and vengeful.

Yes, the comics version had 500% more personality than the movie original

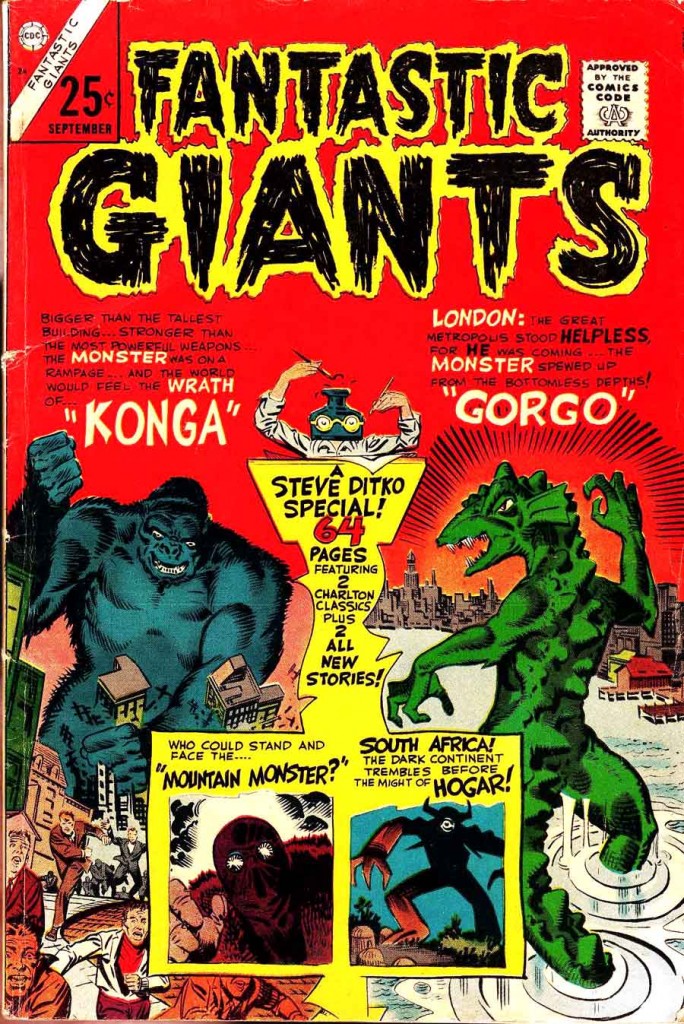

The series was popular enough to last twenty-four issues (the final issue was retitled Fantastic Giants), and it spawned a spinoff miniseries and two companion monster series at Charlton, Gorgo and Reptilicus, both also illustrated by Steve Ditko. Highlights of the series have recently been reprinted in the black and white collection, The Lonely One, which offers terrific reproductions of Ditko’s line art without the distraction of the inferior, crude coloring common to comic books of the 1960s. The stories are absolutely charming and are gorgeous to look at. I highly recommend hunting down either the original comics or the reprint collection.

Even though the final issue of Konga (actually Fantastic Giants) came out when I was a year old, I ended up with a copy as a young boy. My dad worked in a cardboard box factory, and the boxes were made from recycled paper. Knowing how much I loved comic books, he gave instructions to the workers on the factory floor that if they ever saw a comic heading for the shredding machine, they should pull it out and bring it to him. That’s how I ended up with a coverless copy of Fantastic Giants #24, which reprinted the origin stories of Konga and Gorgo, plus two new giant monster stories by Steve Ditko. How I loved that big, fat, 64-page comic! I virtually read it to pieces. I loved it so much that I drew my own cover for it to replace the cover it had lost. Thanks to the magic of the Internet, the real cover of Fantastic Giants #24 is reproduced below:

Oodles of fantastic Steve Ditko art for only a quarter!

For those of you who are big fans of Charlton’s monster movie comics of the 1960s, here’s a link to the mother of all reference articles on the subject, a treasure trove of arcane trivia. Enjoy!

Like this:

Like Loading...