Levi with quad 40mm anti-aircraft mount

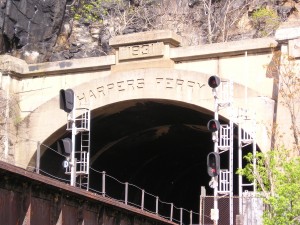

The National Museum of the U.S. Navy is a treasure house, both inside and out. My recent post described the artifacts, some of them gargantuan, that occupy the lawn between the museum’s building and the Anacostia River, where the USS Barry is docked. Today’s post will cover some of the equally stunning (although less large) exhibits found inside the museum hall.

Any fan of the model maker’s art simply must visit the National Navy Museum. When I was a kid, my father, also a military and naval buff, put together plastic model kits for me as birthday and Hanukkah gifts. He built me a Bismarck, a HMS Rodney, and a USS Olympia, as well as a set of Hampton Roads opponents, USS Monitor and CSS Virginia. He regularly took me to hobby shops and to the Dade County Youth Fair, where we could see other model makers’ work on display, some of it very elaborate. However, nothing – absolutely nothing – I have ever seen in the way of scale models compares with the models which awaited me when the boys and I walked inside the Navy Museum.

Armored cruiser USS Pennsylvania

Both Levi and Judah have a funny little habit they engage in whenever something really, really excites them. They jump up and down and flap their arms. Well, I very nearly jumped up and down and flapped like a Canada goose when I saw the first model that awaited us, the USS Pennsylvania, an armored cruiser which served as part of the backbone of the U.S. Pacific Fleet in the first decade or so of the twentieth century, making up part of the “Big Eight” group of armored cruisers. The Pennsylvania is best known, however, as the US Navy’s first “aircraft carrier.” A little more than a hundred years ago, in 1911, she was outfitted with a temporary wooden take-off ramp on her stern and launched seaplanes, which landed in the water and were recovered by ship-mounted cranes. The model on display shows the Pennsylvania in her 1911 state with the temporary ramp installed. This is a big model, easily six feet long, built to a scale, if I remember correctly, of about 1 foot per 100 feet, a scale standard to nearly all the museum’s models.

Monitor USS Miantonomoh

One of the most unusual attractions of the Navy Museum is its outstanding collection of models and artifacts documenting the US Steel Navy, the ships which served from the period stretching from 1890 to the world cruise of the Great White Fleet in 1907-09. One ship which straddled naval epochs, bridging the gap between the US Navy’s ironclad period during the Civil War and its Steel Navy period leading into the Spanish-American War, was the monitor USS Miantonomoh. The history of the Miantonomoh‘s building, and that of her sister ships, is actually more interesting than nearly any of their operational histories. These vessels took longer to construct than any other ships built for the US Navy, reflecting the lowest period in the Navy’s long history. Their construction was begun in 1873 under a cloud of subterfuge. An incident on the high seas nearly led to war between Spain and the United States. The Secretary of the Navy was mortified to learn that the US Navy, had it been called upon to fight the Spanish fleet, had no modern, oceangoing armored ships ready to steam. Congress approved funds for five of the most recent double-turreted monitors to be repaired and modernized; these ironclads had been commissioned in the final year of the Civil War or shortly thereafter. The original Miantonomoh, one of this group, had been the first monitor to cross the Atlantic Ocean, back in 1867. However, by 1873, the five monitors, all with wooden hulls, had deteriorated so badly that they were not worth repairing.

USS Monadnock in heavy Pacific swells

So the Secretary of the Navy used the funds appropriated for repairs to begin building five entirely new monitors, each of which would be given the same name of one of the old monitors, so as to maintain the fiction that those old ironclads were being repaired and refitted. Running out of funds, the Secretary of the Navy gave the private shipyards dozens of Civil War-era monitors and sloops to scrap for additional building money. The scheme eventually came to light, and Congress directed that work on the five monitors be halted. Several years later, however, during another diplomatic crisis, Congress changed its mind and directed that the vessels be completed in various Navy Yards. The incomplete Miantonomoh was transferred to the Brooklyn Navy Yard. However, laggard appropriations and frequent changes in design dragged out construction times for another decade. The Miantonomoh did not enter service until 1891, seventeen years after her construction had been initiated. Her sisters and partial sister, the Puritan, did not enter Navy service until 1895-96, more than twenty years after their construction had begun. Contemporaries and rough equivalents of the British ironclad HMS Devastation, which had been commissioned in the early 1870s, the Miantonomoh and her sisters were thoroughly obsolete as frontline warships by the time they entered service. The major problem with the class can be seen in this photograph of the Miantonomoh‘s sister, USS Monadnock, crossing the Pacific to join Commodore Dewey’s squadron during the Spanish-American War. She made it, but the crossing was so treacherous that she spent the rest of her career on the western side of the Pacific with the US Asiatic Fleet, never daring to cross an ocean again.

Protected cruiser USS Baltimore

The protected cruiser USS Baltimore played a role in every major US conflict from the Spanish-American War to WWII. Commissioned in 1890 as Cruiser #3 of the New Navy, her first major duty was to transport the body of famous engineer John Ericsson, inventor of the US Monitor, to be buried in his native Sweden. She was one of Commodore Dewey’s ships at the Battle of Manila Bay during the Spanish-American War and participated in the Philippines operations which followed that war. Prior to the US involvement in WWI, she was converted to a minelayer, and in 1918 she helped lay anti-submarine minefields between Scotland and Ireland and in the North Sea, an effective deterrent against German U-boats. Between 1922 and 1942 she was laid up as a storage hulk at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii and was present during the Japanese air raid on December 7, 1941.

Broadside 8" gun turret, armored cruiser USS Brooklyn

The USS Brooklyn was the most powerful of the first group of New Navy cruisers, mounting eight 8” guns, four of them mounted in French-style en echelon broadside turrets (one of which can be seen in my photograph of the model of the Brooklyn). Commissioned in 1896, she played a key role in the Battle of Santiago de Cuba in July of 1898, where the main Spanish battle fleet was destroyed. The Brooklyn was hit twenty times by Spanish shells but suffered only one sailor killed. In 1905, she retrieved the remains of naval hero John Paul Jones from Cherbourg, France and delivered them to the US Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, where the body was reinterred. During WWI she served as the flagship of the US Asiatic Fleet and finished her lengthy career with the Pacific Fleet in 1921. The Brooklyn was the only US armored cruiser named for a city, rather than a state.

Battleship USS Kearsarge

Similarly, the USS Kearsarge was the only US battleship not named for a state; rather, she was named after the famous steam sloop of the Civil War, the vanquisher of the Confederate raider CSS Alabama (the museum also features models of the original Kearsarge and the Alabama). Commissioned in 1900, too late for service in the Spanish-American War, the Kearsarge nevertheless enjoyed a very lengthy and varied career in the US Navy. Never firing any of her guns in anger, she participated in the cruise of the Great White Fleet in 1907-09 and served as a training vessel during WW1. In 1920, she was converted to a heavy-lift crane ship. During WWII, she lifted and enabled the installation of guns, turrets, and armor plating for the battleships Pennsylvania, Indiana, and Alabama, as well as the cruisers Savanna and Chicago. She continued to serve as a heavy-lift vessel until decommissioned in 1955, five and a half decades after her first commissioning. The most notable feature of the Kearsarge’s design was her double-decker main turrets, with the turrets for her four 13” guns serving as the bases for turrets for her secondary armament of 8” guns. This arrangement caused blast interference between the 13” and 8” guns, however, and the arrangement was repeated in only one other class of US battleships (the Virginia class).

Ironclad CSS Virginia

Other outstanding models at the museum include a diorama of the CSS Virginia in drydock, completing her fitting out after her conversion from the steam frigate USS Merrimac; the USS South Carolina, the US Navy’s first all-big-gun battleship (designed before the famous HMS Dreadnought but completed several years after that history-making warship); and a tremendous model of one of the navy’s last dreadnought battleships, the USS Missouri. The model of the Missouri was built by the same technicians and craftsmen who built the actual ship; they spent an incredible 70,000 man hours working on the model, which is likely one of the finest ship models existent, anywhere.

Battle flag of USS Balao

The museum contains more than just scale models. There are numerous preserved cannons on display, the largest inside the museum being a twin 5″ gun mount from a WWII anti-aircraft cruiser. My boys enormously enjoyed sitting in the gunners’ seats of a quad 40mm anti-aircraft mount, which they were able to swivel and elevate. A display on American submarines contained fascinating models of some of the earliest US Navy submersibles, as well as two working periscopes, both of which poked out the museum’s roof and looked out onto the USS Barry. Another wonderfully appealing artifact is the battle flag of the submarine USS Balao, credited with sinking seven Japanese vessels in WWII. This memorable flag, with its cartoon mascot of a pistol-packing bumblebee riding a torpedo, was designed by a Walt Disney Studios artist in 1945 at the request of Motor Machinist’s Mate 3rd class William G. Hartley.

We’ll most definitely go back. Many times!

Like this:

Like Loading...