The death of Borders Books (and let’s not forget the associated death of subsidiary WaldenBooks, once a huge force in book retailing) has many people prognosticating about the future of physical bookstores. As a writer, a reader, and a lifelong aficionado of bookstores, I’d like to jump into the conversation.

An old, if somewhat inaccurate, adage tells us that the Chinese word for “crisis” is made up of two characters, one representing “danger” and the other “opportunity.” The “danger” part of the dissolution of Borders is clear enough. Nearly 11,000 people employed by Borders Books and WaldenBooks will lose their jobs. An unknown number of publishing employees whose sole or primary responsibility has been to take care of the Borders account will also lose their jobs. For writers and their readers, the danger is that the loss of so much retail shelf space is going to slash the numbers of titles which are green-lit by publishers, as explained in an article from National Public Radio called “Bye Bye Borders: What the Chain’s Closing Means for Bookstores, Authors, and You“:

“Kathleen Schmidt, a book publicist, provided this perfectly concise explanation on Twitter: ‘Here is how the Borders closing will impact publishers: Say you have a bestselling author and you usually do a 1st printing of 100K books. Out of that 1st print of 100K, B&N/Amazon would take a large quantity, then Target, maybe Costco/BJs/Walmart, then Borders, then indies. If you’re an author with a 1st print of 30K (a lot), you prob don’t have price clubs or Target. You have B&N, Amazon, Borders, and indies. Now, take Borders OUT of that 1st print equation. Also consider that B&N is conservative with numbers these days. That 30K turns into 15K.'”

For the major publishers, 15K of anticipated sales is the borderline between green-lighting a trade paperback novel and rejecting the author’s manuscript. The likeliest outcome of the disappearance of all those shelves at Borders is that fewer projects will get past the Profits and Loss Departments of the Big Six publishing houses. Some of the slack may be taken up by smaller, independent publishing firms, but they will be affected by the loss of retail shelf space, too. Their “go/no go” borderline may be 3K sales, rather than 15K sales, but they are still faced with the same arithmetic. The departure of Borders will hasten the exodus of many lower-selling writers from traditional print to e-book originals and print-on-demand.

Any shift away from printed books to e-books would seem to be certain to hurt the surviving physical bookstores (although many independent bookstores now make it possible for their customers to order Google Books through them). Independent booksellers have experienced a modest resurgence in recent years; after fifteen years of steady decline, the American Booksellers Association, the trade group of independent bookstores, reported a 7% increase in the number of member stores in the past year. However, some independent bookstores which have managed to survive thus far in the shadows of Borders may actually be swamped by the wake of Borders’ sinking:

“‘What troubles me,’ says Susan Novotny, owner of Book House of Stuyvesant Plaza in Albany and Market Block Books in Troy, N.Y., ‘is having them [Borders] in a constant state of giving away books.’ She worries about ‘a hang-over effect’ from customers who are booked out.”

So there we have the “danger” part of “crisis.” What about the “opportunity” part?

I believe physical bookstores provide a vital element of what sociologist refer to as “the third space.” The first space is the home, the second is the workplace, and the third space is, like the classic French cafe or the English pub or (in the 1950s and 1960s) the American bowling alley, the place where people go to spend their leisure time among other people. One thing that the expansion of Borders (and Barnes and Noble and Books-a-Million) did over the past twenty-five years was to give a taste of bookstores-as-third-space to millions of people who previously had no bookstores to call their own. Prior to the mid-1980s, hundreds of metropolitan areas, either small cities or the suburbs and exurbs of big cities, had no access to a local bookstore of any type (aside from maybe a used paperback exchange kind of place). But the megastores gave the residents of those areas their own local bookstore, a place to hang out that didn’t involve alcohol, a place to meet friends for coffee or sit in the cafe area and peruse a magazine or a new book. For many people, their local Borders or Barnes and Nobles came to serve as a kind of community center, or that special kind of place where you can go to be alone, but among other people. Many independent bookstores offer these same amenities and may even do them better, but the megastores planted themselves in many places where no independent bookstores had gone. When 400 Borders stores close down, that is going to leave a void in a lot of people’s lives, a void that can’t be readily filled by bars or restaurants. The Borders store closing in Scranton, Pennsylvania is the last bookstore in the entire city; the smaller chain bookstores located in malls closed in the mid-2000s, along with two independents. Bookstore regulars in Scranton fear they will have nowhere else to go.

Where enough demand exists, entrepreneurs find ways to meet those demands. Joseph Robertson is bullish on the future of independent bookstores. His recent article, “Borders Closure is Green Light for Bookstore Innovation,” lists four innovations which may help new (or newly revitalized) independent bookstores to thrive in many markets:

“The true cafe/bookstore: A more balanced relationship between the bookstore and cafe sections of a retail space, with high quality coffee, with events and music, gatherings and opportunities to sit down with authors, and a bookstore that echoes this quality with content.

“The information oasis: Bookstores can reposition themselves as trusted sources of information, stocking quality publications, some new to newcomers, and unique titles with real depth and scope, understood by intelligent, engaged buyers and salespeople. Mainstream media may be an echo-chamber, but bookstores can be places where the individual is free to think for herself.

“The genius bar: One of the reasons Apple’s stores are popular with Mac lovers is that they provide information and knowledge that is useful; customers can learn from staff. Bookstores could make sure to be a source of guidance to the reading public, taking back that role from distributors and advertisers and being more pro-active about deciding what they stock.

“The cyber-paper crossover: Barnes and Noble, BN.com and the Nook, have made for an impressive collaboration. Small bookstores can take Borders’ market share, collectively, if they learn the lesson Borders missed: assist your readers in all media, and they will stand by you. Wifi is useful, but dedicated new-fangle web access, whatever that looks like, could help bricks-and-mortar independents sell print books.”

I would add a few suggestions to Robertson’s list:

The child-friendly bookstore: Borders was actually fairly strong in this regard with their designated children’s play and reading area and their Saturday afternoon story hours and activities for children. We parents are always looking for good indoor activities for our kids, perfect for those times when you just have to get them out of the house but inclement weather prevents you from taking them to a park or a playground. My local Borders stores were always very welcoming to my kids, and on days when they catered to children, crowds in the stores were healthy. I think one way in which Borders got themselves into trouble was their selection of locations. A good number of their stores were in areas which commanded extremely high rents. The stores may have succeeded in attracting a steady flow of customers, browsers, and folks who brought their kids for events, but their overhead was so stratospherically high that they suffered losses year after year. Corporate leaders were seeking status locations, locations which would allow them to build the Borders brand as upscale and somewhat exclusive, but the items their stores sold weren’t high margin enough to pay the rents. Independent bookstores typically don’t have owners who are slaves to prestige. Owners of non-corporate bookstores are often cannier about their locations than their corporate counterparts and are free to select locations in underutilized, lower-status retail areas which, although commanding much lower rents, may have unique advantages particular to a given neighborhood (nearness of restaurants or other centers of social activity; located in an area being gentrified by artists; etc.), advantages not so visible to an owner who doesn’t live in the community.

The rebirth of the newsstand: Mitchell Kaplan, owner of the local Books and Books chain of stores in South Florida, is pioneering this idea. He started with his original store in Coral Gables, a traditional full-service independent bookstore, but several of his other locations are very different. His notion was to replicate the magazines and cafe sections of Borders or Barnes and Noble but in a smaller, more intimate size, appropriate for tight spots in areas with high levels of foot traffic, such as South Beach or the Bal Harbour Shops. The wide variety of magazines gives Kaplan’s spinoffs a leg up on Starbucks or other corporate coffee houses and makes his locations much more of a destination for couples out on a date or individuals looking to spend a pleasant hour or two. A carefully and intelligently curated small selection of books would also add to the allure of a newsstand/coffee bar. Books were once widely available at newsstands. I think they should be again.

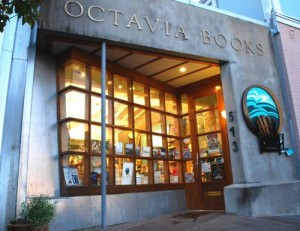

The center for writer-reader interaction and reader-reader interaction: My favorite independent bookstore in New Orleans, Octavia Books, is very good at this. Owner Tom Lowenberg swam against the tide and opened his store a little more than a decade ago, when hundreds of independent bookstores were dying off each year. He has built an extremely loyal customer base by making Octavia Books a headquarters for readers’ encounters with writers and readers’ encounters with each other. In addition to hosting five or six author events each week, Tom also makes his store available to a wide variety of reading groups, providing them complimentary refreshments and a familiar, friendly face.

Bookstores of the future may need to become more like microbreweries, focusing on their uniqueness, their sense of their region and neighborhood, and their owners’ personalities. More and more books may be consumed in the form of pixels, rather than ink on paper. But I believe physical bookstores will continue to exist and thrive as a vital and beloved “third space.”