Anne McCaffrey, superstar science fiction writer, author of 83 books (71 science fiction novels and short story collections, 2 cookbooks, 6 romances, and 4 juvenile fantasy novels), and the 22nd author to be named by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America as Grand Master, passed away last week on November 21, 2011. She was eighty-five.

Her accomplishments in the field of science fiction tower as high as the flights of any of her dragons or sentient spaceships. She wrote and sold her first science fiction story in 1952. Her second story, “The Lady in the Tower,” was published soon thereafter in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction and was selected by Judith Merril for her annual collection, The Year’s Greatest Science Fiction (certainly an auspicious start to a career!). Anne won her first Hugo Award in 1968 for the initial story she wrote about the dragonriders of Pern, “Weyr Search.” She was awarded a Nebula Award the following year for her second Pern tale, “Dragonrider.” In 1978, her novel The White Dragon, third book in the Dragonriders of Pern series, became one of the very first science fiction novels to hit the New York Times Best Seller List in hardback. Since 1978, her books have sold millions of copies around the world. She and her characters inspired the creation of one of the largest annual popular culture conventions on the planet, Dragon*Con, second in immensity only to Comic Con International.

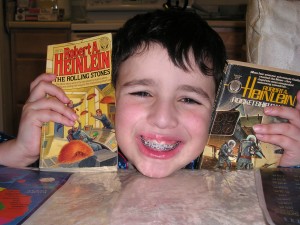

Her early novels helped turn me into a science fiction fan (I was able to cajole my parents into buying me a hardback copy of The White Dragon when it was first published by Del Rey/Ballantine in 1978, having read and fallen in love with Dragonflight and Dragonquest the year before). Yet great as the impact she had upon me as an author, she had an even more powerful impact upon me as a correspondent, supporter, and friend. Wonderful as Anne was as a writer, she was even more impressive as a gracious, generous human being.

I wrote my first fan letter to Anne in April, 1978 and sent it to her care of her publisher, not realizing my letter would be forwarded all the way to County Wicklow, Ireland. I only have copies of the first two letters I mailed to Anne, and I only have those because they were published in a professional journal (more on this odd circumstance to follow). Somehow, in my many moves since my teen days, I managed to lose some of the letters Anne sent me, but I have retained most of them. I don’t think she would have minded my quoting from them. Even thirty-three years later, I am still bowled over by the fact that such a busy woman (she wrote 83 books, after all!) took the time to correspond with a young teen across the Atlantic Ocean. And I will always remain immensely grateful for the thoughtfulness, care, and enormous generosity her letters showed.

April 24, 1978

Dearest Ms. McCaffrey,

My friends and I would like to sincerely thank you for the pleasure your works in the SF field have brought us. I was introduced to your writings through your fabulous Dragonriders of Pern series, and I have been impatiently hunting down your books ever since (I cannot wait until Dragonsinger makes its appearance in paperback). I immediately lent Dragonflight to my close friend Robert Danburg and he was similarly impressed. In fact, your books gave us the stimulus to form our own group—the Dragonriders. In a fit of creative inspiration, we decided to publish our own fanzine, to be called The Dragon Reader.

I have always held a love for creative writing, especially SF and fantasy, so I envisioned The Dragon Reader as a showcase for young writers, as well as an aid for them in breaking into the field (I admit the notion was a bit self-centered). By extreme good luck I was able to get newspaper coverage, and I include the article in this letter.

We hope to be publishing by August, and we hope that we may secure an interview with you for a future issue. …

Sincerely,

Andrew Fox

[Unfortunately, I no longer have the first letter Anne wrote back to me, so I’ll continue with my second letter to her.]

May 19, 1978

Dearest Ms. McCaffrey,

I simply can’t thank you enough! You have no idea of the thrilling experience it was to actually communicate with you. And your letter surpassed my highest expectations. I expected at most a mimeographed letter from your literary agent telling me in a polite way to go dig a hole for daring to ask to write stories utilizing your characters. Yet I received a hand-typed letter from you yourself–even Robert replied with an uncharacteristic “Oh wow!!!” Your reply gave us a boost of indeterminable magnitude.

Since I first wrote you, the Dragonriders have received an additional five members. Unfortunately, none of them are familiar with your works, so I had to introduce all of them to you. Within a few weeks, however, they’ll all be as nutty about you as I am.

At first I was afraid that the group and the magazine would be too fantasy-oriented, but many of the newcomers are into “hard” SF, so there should be a healthy balance there. Things seem to be going extraordinarily well, and if luck finds favor in us, we should be seeing Dragon Reader 1 by the end of August. We have held two meetings so far, and I see a few wonderfully creative fanatics among the newcomers, the second meeting being broken up by a furious argument between Preston and Seth over whether or not the fourth dimension if an alternative universe or a fourth plane of existence. …

Since I wrote to you, I have read The Ship Who Sang. Another pearl in your necklace of masterpieces. My pleasure at reading this book was only equaled by Dragonflight, my introduction to your works, and Robert Silverberg’s Nightwings. I later bought Get Off the Unicorn, and “Honeymoon” was the first story I read. Helva was a wonderful experience, and I know I’ll be seeing a lot more of her, whatever name she goes under. Characters are mirrors of their author, perhaps one facet of that author, but a part nevertheless, and through writing, a person discovers much about him or herself. This is what pulls me to writing. Many people look down upon others for vigorously reading fiction, which they dismiss as non-reality. But if fiction is non-reality, then how does one account for the effect it has upon people, producing joy, thoughtfulness, or perhaps even tears? Non-reality could not do this. Non-reality is nothingness. Perhaps the imagination is a separate reality, a fresh horizon that man can never fully explore. These realities are strongly connected, for isn’t imagination contributing to “reality” every day? Thanks for helping all of us to discover that separate reality, and through it, discover a bit more about ourselves. And don’t you be surprised if someday that golden form flying high above you isn’t an airplane at all. …

Sincerely,

Andrew Fox

****

27 May 1978

Dear Andrew,

And you, my young friend, do not know how thrilling it was for me to read your letter of May 19. Because, Oh Wow! did you solve my problem.

You see, American Library Association asked me to speak to their young adult division in Chicago on June 26 and I’ve been trying to write a proper type speech for such a prestigious group. There seems to be some controversy in ALA about the needs of boys and girls about your age, and how to supply them with library materials and books. Of course, I can’t think of any better way to get young people reading than handing them as much good science fiction as you can find–or good historical fiction with, preferably, well developed young adults as heroes and heroines. I watched my own three soak up information on all levels. The trick is getting people into the habit of reading. By writing, as in your case.

But I couldn’t seem to come up with a hook to hang the speech on. OH, sure I’d mention the dragons, and Helva, but I wanted to say something special to the good people of ALA. YOU, bless your cotton-picking heart, have provided me with that hook. You said in your letter, “Many people look down upon others for vigorously reading fiction, which they dismiss as non-reality. … Perhaps the imagination is a separate reality, a fresh horizon that man can never fully explore. These realities are strongly connected, for isn’t imagination contributing to ‘reality’ every day? Thanks for helping all of us to discover that separate reality, and through it, discover a bit more about ourselves.”

Hey, man, those are marvelous words and if your ‘zine DRAGON READER reflects more of some very sensible ideas from its editor, it’s going to be one of the top ‘zines in the country!

Thank you, my friend, for one of the best and wisest letters I’ve ever received from a fan.

I’m also sending you under separate cover a little present which I hope you will share with your team, Robert and Raymond, and those joining the Dragonriders. More available on request!

Again my heartfelt thanks for getting me out of a pickle. I’ll keep your phone number with me so I can call… and, honey, that call’s on me!

Fondest best wishes,

Anne

[Anne sent us dragonrider buttons and teeshirts, which we all proudly wore for years, until they wore out from repeating washings. The editors of Voice of Youth Advocates were so impressed with Anne’s speech to the ALA that they requested a copy of it, then contacted me to ask whether I’d agree to have my letter reprinted in their journal. As you might well imagine, I was thrilled. My family and I visited England in early summer of 1978, and Anne and I tried to connect by phone, but unfortunately didn’t manage to hook up.]

10 July 1978

Dear Andrew,

I did try to reach you–in fact, made a note of the time–Wednesday, 5 pm, June 21, and again on Thursday, June 29. No luck both times. I was so heavily scheduled and either flying or signing books in the mornings, and then dining out until far too late to make an evening call permissible or pleasant for your family. I was disappointed, too, because I wanted you to know that I ended my ALA speech with your words and they got a big round of applause from the 600 young adult librarians who attended that luncheon. I have also been asked for your letter by Mary K. Chelton (a former president of ALA) who publishes a magazine to aid YA librarians. I didn’t think you’d mind but she may be writing for permission from you as well, just to keep things right.

Would you believe it, though, they were selling tapes of my ‘speech’ for $8 after the luncheon! Young man, you have achieved a measure of success already. However, I know you’re the sort to keep your cool. Even if you live in Florida. …

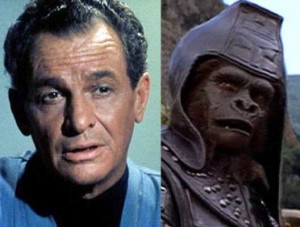

Your notions about movies for the Dragon books, not to mention your picking Ray Harryhausen and Jim Danforth, are spot on. There are film options against DRAGONFLIGHT, SHIP WHO SANG, and DECISION AT DOONA. Of course, there’s a long way between the option and the making. Lots of very good s-f stories have been optioned for years, and no movies forthcoming. DECISION AT DOONA, though, looks to be an exceedingly good proposition. It would be filmed here in Ireland as I have been able to keep my paws on the script writing and consultancy for that film. You’re perfectly right that modern screen technology makes the possibility of dragons, good Pernese dragons, feasible, but for Dragons, one has to think the neighborhood of $15-$20 MILLIONS. Not easy to raise, whereas DECISION could be brought in at about $2-3 millions… much easier to film with the right sort of make-up for the Hrrubans and Jim Danforth is one of the men the producer is trying to interest in the movie. (Ray Harryhausen has been approached several times about doing the dragons of Pern but has not snapped at the bait. Too bad: his creatures in The 7th Voyage of Sinbad were impressive.)

There is one disadvantage about filming the Dragons of Pern: too many people have imagined them privately and I don’t see any way (since I’ve already received a startling number of ‘dragon’ sketches and sculptures) that the variety of notions as to what Pern dragons really look like can meet in a compromise. The man who bought the film rights, for instance, insists that Pern dragons have ears! I have argued that they don’t need ears, don’t have ears, and forget the illustrations he’s seen! His wife, who is as interested in the project as he is, feels that they should have fangs and the longer, reptilian neck. One can’t please even two people, much less the new s-f audiences.

I was very pleased to see that Ursula’s THE LATHE OF HEAVEN would be televised. Read the article in TV Guide, and as they have had the good sense to hire her as a consultant, perhaps the translation from printed word to celluloid will please those readers who have so enjoyed her books! And there is always the possibility that one of my SHIP stories, or even WEYR SEARCH might follow if LATHE proves successful. I don’t give up hope, but I also don’t hold my breath. Movies are pie in the sky as far as I’m concerned.

I do hope that you have a pleasant summer–and get some work done. Again, I regret I couldn’t reach you by phone… my timing sure was off!

Sincerely,

Anne

Anne and I continued corresponding for the next few years. That first issue of The Dragon Reader didn’t appear until the summer of 1980; putting together a magazine was much more labor intensive in the days before desktop publishing, and my friends and I kept changing the magazine’s contents, never feeling quite satisfied with our stories or artwork. But we finally got that first (and only) issue in print, just in time to take it with us to Noreascon II, the 1980 World Science Fiction Convention in Boston. I’ll quote from some of her other marvelous letters, which are full of great nuggets and anecdotes for her fans and readers, in another few days.

Anne and I only got to meet in person once, in New Orleans in 1995 or 1996, not long after I’d joined George Alec Effinger’s fiction workshop group. Anne had come to New Orleans on family business and did a signing at a Waldenbooks at the Oakwood Mall, a store where a friend of hers worked. I saw a notice in the newspaper that she would be there, right across the Mississippi River from where I lived, and made certain to take off from work so I could be there. Her signing, surprisingly, was uncrowded, so we got about twenty minutes to talk before she had to leave. We hadn’t exchanged letters in almost fifteen years. She was at a loss as to who I was for half a minute, but once I reminded her of her speech to the ALA in which she’d quoted me, she remembered me and greeted me very warmly. I quickly caught her up on all that had happened in my life since my friends and I had put out that one issue of The Dragon Reader — where I’d attended college, my recent marriage, my job with the Louisiana Office of Public Health, and the dark fantasy novel I’d been workshopping with George Effinger’s group. I told her I might never have had the confidence to submit stories to magazines and to write a pair of novels if she’d hadn’t been such a wonderful and supportive friend when I was all of thirteen years old. I told her she had provided my role model of how a writer should ideally interact with his or her readers–should I ever be fortunate enough to acquire any readers, I said, I would try to live up to her example.

I’m so glad I took that opportunity to see her and to thank her for all the inspiration and support she had given me. Because I never did find myself with another opportunity to meet with Anne McCaffrey. And now, sadly, I never will.

Like this:

Like Loading...