This past Sunday, I took my three boys to a local carnival, set up in the big parking lot behind the Potomac Mills Mall in Woodbridge, Virginia. The carnival was running a “threatening weather special” on unlimited rides bracelets, and between the special and a set of $5 off coupons, I was able to buy each boy a bracelet for $15 apiece, which seemed reasonable (especially given that buying ride tickets would mean spending $3 or $4 per ride per child, which would very quickly eviscerate my wallet).

When I was a kid, I was a tremendous fan of carnival rides. I begged my parents to take me to any neighborhood or church carnival I heard about, and I’d squeeze in as many rides on the Zipper, the Octopus/Spider, the Tilt-A-Whirl, and the Rock-N-Roll as I could.

My longest continual carnival ride came in high school, when my theater club, the Pioneer Players, raised funds for our trip to the State Thespian Competition by hiring out all the members of our club as extras on the set of the low-budget horror film, The Funhouse, directed by Tobe Hooper and filmed in North Miami in 1981. Nearly all of the film takes place on a carnival midway, and the filmmakers needed hundreds of extras to ride the rides and play games and walk around eating corndogs and fried dough. (The filming took place on the grounds of the old Ivan Tors Studio on 125th Street in North Miami, where Flipper and other TV shows had been produced.) My job turned out to be riding the Sizzler, which twists and twirls you around and around and around. Turned out I had to ride the Sizzler for more than five hours straight, from about 9 PM to 2 AM. On a very chilly night (for North Miami, that is… it was probably in the 50s). Good thing I had a strong stomach back then. I doubt I could handle the Sizzler for five minutes straight at my age now, much less for five hours. The producers called things to a halt a little before 2 AM and invited all us extras into a chow tent for some hot chocolate and hamburgers. By that time I was very hungry and VERY cold (not to mention very tired), so I appreciated their largess.

Anyway, my kids are about as nuts for carnival rides as I once was. So I felt really good about being able to buy them unlimited rides bracelets, which meant I wouldn’t have to carefully ration their rides, like I had during every other trip to a carnival we’ve made as a family. My surprise of the afternoon was how good I ended up feeling about the workers on the midway. There is a widespread stereotype of carnival workers (“carnies”) being, well, skeevy, greasy, ill-mannered, and generally unpleasant. I won’t say that I’ve never had the displeasure of interacting with carnival workers who lived down to the stereotype. However, that didn’t occur at this carnival, operated by Dreamland Amusements. The workers I had the pleasure to interact with were friendly, helpful, and attentive to my anxiety that my kids should be properly strapped and buckled into rides (I almost had a panic attack when I saw that Judah, my five-year-old, had wrapped the bumper car seat belt around his neck after climbing in next to his older brother Levi, but the operator assured me he would sort Judah out, and he did).

One employee was especially friendly, talkative, and helpful. He operated a ride called Anchors Away, a pair of pirate ships that swung on half-moon-shaped tracks, giving the riders a cascading back-and-forth swinging ride (there’s a photo of the ride at the top of this post). All three boys initially rode Anchors Away together. The operator, a man in his sixties, surprised me by showing genuine enthusiasm for children, a quality I don’t typically see in this sort of setting – he laughed with them and encouraged them to raise their arms into the air while the ride swung them back and forth. At first, I wasn’t sure that Judah was enjoying himself. He had a very disconcerted expression the first couple of swings. But then he raised his arms like his brothers were doing, and by the end of the ride he was smiling and laughing. They all asked to ride it again, and since they had ride bracelets, I said, “Sure! Why not?” But when his two older brothers said they wanted to go next door to ride the Sky Hawk, a ride too advanced for Judah, Judah said he wanted to stay and ride Anchors Away some more.

He ended up riding it eight times in a row, and he would’ve kept right on riding it if I had let him. Once, when there were no other children or adults in line with him, the operator even let him ride it all by himself. The operator told me that recently, at a State Fair in Tampa, Florida, a mother had let her little girl, about Judah’s age, ride Anchors Away all day long. I noticed a sign hanging from the guard railing surrounding the ride. It gave a brief history of this particular Anchors Away ride, one-of-a-kind. The ride had been designed by Bruce Sellner, president of Sellner Manufacturing of Faribault, Minnesota, in the mid-1990s. Mr. Sellner had intended for Anchors Away to become a new mainstay of Sellner Manufacturing. However, he passed away shortly after designing the ride and seeing the first one built, and the company decided that it would build and sell only that initial unit. (Did they do this as a memorial for Bruce Sellner? It seems like a better memorial would’ve been to keep building more units of the last ride design he had championed. But maybe his family members who took over the business after his death decided the business model for making more of them no longer stood.) The one and only Anchors Away was sold to a West Coast carnival company, which owned it until last year, when Dreamland Amusements bought it. The sign announced that Dreamland Amusements was proud to bring the only Anchors Away to carnival-goers on the East Coast for the first time.

I wish more carnivals would do this sort of thing – publicize what is unique about their rides and attractions. I’m sure individual rides must take on lives and histories of their own, considering that many of them travel around the country for decades. The rides at Dreamland Amusements range in age from at least my age (I was born in 1964) to less than a year old (they purchased their one-truck Himalaya ride, manufactured by Wisdom Rides, in 2011, and their Dizzy Dragons kiddy ride is also pretty new). The oldest ride I saw probably dates to the mid-1960s; it was a kiddy automobile racing ride, with miniature cars mounted on a turntable. I can pretty much date it to around 1965 or 1966 because all of the cars were either first generation Ford Mustangs (first built in 1964) or early 1960s Corvette Mako Shark concept cars (the concept car precursors to the second generation Stingray Corvettes that came out in 1968). That modest little ride has seen quite a lot of use; how many thousands of kids have sat inside those miniature Mustangs and Corvettes and twirled their steering wheels over the past forty-five years? It is a little staggering to think how many times the ride has been put together and taken apart during its career, considering that it gets disassembled at the end of each show, mounted in pieces on a truck, then reassembled at the next show a week or two later. I’ll bet the long-time carnival workers get pretty attached to and sentimental about the rides they work with, considering that they take them apart and put them together probably between twenty and thirty times each year, then spend long hours operating them in-between.

The day after taking the kids to the carnival, I looked up the history of Sellner Manufacturing, the makers of the one and only Anchors Away. The company got started way back in 1923 by Herbert W. Sellner (grandfather of Bruce Sellner, who invented Anchors Away). The first ride Herbert manufactured was the Water-Toboggan Slide, designed for swimming parks on lakes. Boy, does that look like it was fun! Check out these photos. Can you imagine riding a toboggan down that long, tall, steep slide, then skimming a hundred feet across the surface of a lake? What a thrill that must’ve been!

But Sellner Manufacturing’s biggest success and greatest claim to fame rolled out a few years later, in 1926, when Herbert Sellmer invented the Tilt-A-Whirl. They manufactured hundreds of the original design, and they continue to build updated models today (Sellner Manufacturing, a family-owned company for most of its existence, was purchased by Larson International in 2011).

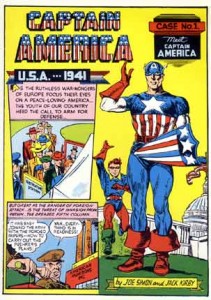

Take a look at this photo of a Tilt-A-Whirl from the 1940s. I’ll bet lots of readers my age or even a little younger will recognize the design. I rode Tilt-A-Whirls exactly like the one in the photo throughout the 1970s, and I’ll bet if I were to rent a copy of The Funhouse from Netflicks, I’d see one of the old-style Tilt-A-Whirls spinning on that haunted midway where I rode a Sizzler for five hours straight.

Just for comparison’s sake, here’s a photo of a modern-day Tilt-A-Whirl, a custom designed Mardi Gras version Sellner Manufacturing built for New Orleans’ City Park Story Land after Hurricane Katrina destroyed all of the park’s original amusement rides.