Who says the mega theme parks, the Disneyworlds and Sea Worlds and Six Flags, have killed off America’s traditional roadside attractions? Those durable, lovable staples of summer road trips may be ailing, but they aren’t quite dead yet. And if “the poor man’s Walt Disney,” Mark Cline, has any say in the matter, the old-fashioned roadside attraction will never die.

Over this past Memorial Day Weekend, my family and I took a road trip to Natural Bridge, Virginia. Our goals were to see the Virginia Safari Park (very much worth seeing, by the way) and the famous Natural Bridge monument and park, one of the natural wonders of North America. While driving on U.S. Highway 11 toward the center of the town of Natural Bridge, we passed several signs advertising a free attraction called Foamhenge. This sounded like something very much up our alley (aside from being free, which sounded good after the $$ we’d dropped at the safari park). So we put Foamhenge on our agenda for the afternoon, following our visit to the Natural Bridge monument and park.

The ticket takers at the Natural Bridge Park told us Foamhenge was definitely worth seeing, and that the man who had created Foamhenge had also operated a family attraction next to the park called the Haunted Monster Museum, which had burned down the year before (this unfortunate news greatly disappointed the boys and me). Foamhenge, a short drive away, turned out to be fabulous, in a tacky sort of way, a full-sized, accurate reproduction in Styrofoam of the world-famous Stonehenge in England. Reading the signs that adorned the little site, I discovered that the creator of Foamhenge, Mark Cline, had a wonderfully wicked sense of humor. He also appeared to be a talented maker of fiberglass figurines, judging from the impressive Druid priest who “guarded” the installation.

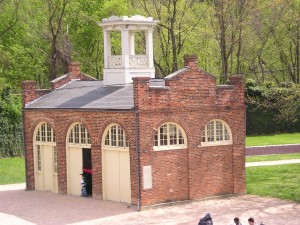

Also along U.S. Highway 11, we spotted a ramshackle compound called the Enchanted Castle Studio. A wooden wall surrounded most of the compound, but we could see the tops of numerous enticing dinosaur figures inside, as well as the tops of various mythological creatures and heroes rendered in fiberglass. Off to the side of the walled part of the compound lay an abandoned castle-type building and several very weird giant figures, including a massive blue and yellow insect that we took pictures next to.

On the drive home, I promised myself to learn more about this Mark Cline fellow. Little did I know then that I had already seen numerous examples of his work, at Dinosaur Land in White Post, Virginia, and in the parking lot of the Pink Cadillac Diner just outside the entrance to Virginia Safari Park. Nor could I suspect how fascinating the story of his career would be… the story of one of America’s great roadside attraction impresarios. Beset by adversities and setbacks which would have stopped most other entrepreneurs’ careers cold, Mark Cline has gone on and on and on, never ceasing his search for that pot of gold at the end of a fiberglass rainbow.

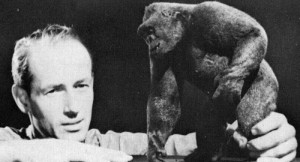

Mark Cline, born in 1961 (three years older me), and I lived almost parallel childhoods. We both spent our youths filming our own monster movies and building miniature monsters and dinosaurs. The major difference is that Cline ended up going a whole lot farther with his artistic pursuits than I ever did (I got sidetracked into acting, first, and later writing). During his teen years in Waynesboro, Virginia in the 1970s, Cline made his own Super-8 horror movies and helped build sets and props for a local monster movie show. His latex monster creations won awards in local art competitions. He learned the art of sculpting in fiberglass during a job at Red Mill Manufacturing in Lyndhurst, outside Waynesboro, a company which manufactured small resin figurines, including Minutemen and turtles, for souvenir and novelties stores. His mentor at the company showed Cline how to make a mold of his own hand, then sent him home one night with a five gallon bucket of resin to experiment with. In 1982, hoping to achieve his childhood ambition, he attempted to start up his own horror-themed roadside attraction in Virginia Beach, but, without any business expertise or experience, he failed miserably.

However, on his drive home, he ran out of gas in Natural Bridge, Virginia, a small town whose major claim to fame is the privately-owned Natural Bridge monument and park, then surrounded by several downscale roadside attractions. He decided to make a second attempt to start his own business. Later that year, he opened his first version of the Haunted Monster Museum in Natural Bridge, but his attraction was shunned by the operators of the nearby Natural Bridge park, and it closed after three years. He reopened it shortly thereafter, retooled as the Enchanted Castle, and began a more collaborative relationship with the owners of the Natural Bridge park, who began selling tickets to his new attraction at their own well-attended facility. The Enchanted Castle featured a bungee-jumping pig, leprechauns, fairies, a giant-sized Jack-in-the-Beanstalk, plus weirder creations, such as a tremendous tick, a “Holy Cow” (cow with wings), and a 15-foot-tall devil’s face guarding the park’s entrance. In retrospect, given what was to happen a few years later at his small park, perhaps he would have been prudent to skip the devil’s face, which apparently did not sit well with the more religiously minded among his neighbors.

On the grounds of the Enchanted Castle, Cline founded his Enchanted Castle Studio, where he created new fantastical fiberglass creations, not only for his own attraction, but for other businesses, as well. A fortuitous chance meeting with either William Hanna or Joseph Barbera (Kline can’t recall which of the men he talked with) at a trade show resulted in Kline winning a contract to supply ten-foot-tall fiberglass Yogi Bear statues to all 75 of the country’s Jellystone Park Campgrounds. In 1987, Joann Leight, the daughter of the original owner of Dinosaur Land (opened in 1963), hired Cline to create a new group of more up-to-date, dynamic dinosaurs for her roadside attraction near Winchester, Virginia. Mark had visited Dinosaur Land as a boy, and that visit had been one of the primary inspirations for the direction his life’s career would later take.

“‘My father and I were traveling, coming back from Baltimore, and Dinosaur Land [in White Post, Virginia] was closed, but I asked my dad to stop there—I’d been there before—and he said, “OK.” I was probably about 12 years old. We stood there together looking through the fence at these huge dinosaur figures, and I said, “I’m going to make these when I grow up, dad.” And he just said these 11 words to me: “If that’s what you want to do, nothing can stop you.”’”

Cline, in addition to being a businessman and artist, has always been a trickster. April Fools’ Day is one of his favorite holidays. However, one of his theatrical holiday pranks, intended to amuse his neighbors and drum up additional business for his Enchanted Castle attraction in 2001, resulted in a major setback, an apparent arson which nearly ended his career as a roadside impresario.

“A couple of weeks before the blaze, Cline played a prank on the neighborhood by scattering a handful of ‘flying saucers’ and ‘aliens’ along Route 11, the main drag through Rockbridge County. In the spirit of the neighborhood, the saucers were crafted from discarded satellite dishes. In the spirit of a true entrepreneur, they were subtle lures to his ill-fated tourist attraction.

“On April 1, 2001, the stunt and its maestro were revealed (as if there were some doubt) in a story with color photos on the front page of the Roanoke Times. The blaze occurred eight days after the story was published. … Since the October before the fire, Cline says, he had been finding religious tracts tucked under the wiper blades of his pickup truck … On the night of the fire … he went out to his mailbox to find a more ominous tract.

“‘We have prayed for you,’ read the hand-written letter, which also accused Cline of ‘darkness’ and ‘beastly madness.’ The writer warned that ‘the wrath of God is very fierce.’ Included was a burnt-around-the-edges copy of Cline’s photo clipped from the Roanoke paper.

“‘Fire represents God’s judgment,’ the letter closed. ‘Behold, the judge is standing at the door.’

“‘I read this as I was watching the castle burn,’ says Cline. … Cline, who received an insurance settlement for his buildings but not for the contents, readily concedes that he was a suspect. He says that before the flames were fully extinguished, he and his wife were separated and interrogated.

“‘I know who left me the messages,’ says Cline. ‘But there’s no proof they actually set the fire. It could have been oily rags or lightning– I believe in coincidences too.’”

Not a man to be deterred by adversity, a year later, in 2002, when the owners of Natural Bridge park offered Cline a lease on a rundown Victorian mansion on their property, Cline decided to begin anew, and he turned the old mansion into his Haunted Monster Museum & Dark Maze.

The following year, seeking to expand his empire of southwestern Virginia roadside attractions, Cline decided to go bigger. He turned the faded boomtown of Glasgow, Virginia, six miles from Natural Bridge, into “The Town that Time Forgot.” Cline made agreements with the owners of a dozen or so Glasgow merchants to allow him to put one of his life-sized fiberglass dinosaurs on their property, either on their lawn, in their parking lot, or even atop their building. Then he convinced the town government to pay for 50,000 copies of a promotional brochure he had created. The town fathers, initially convinced that Cline’s creations would help put them back on the map, gave a green light to the plan. So on April Fools’ Day, 2003, Glasgow became the dinosaur capitol of southwestern Virginia. However, Cline’s dinos didn’t pull in as many visitors as the Glasgow authorities had hoped for, so a year later, they pulled the plug on Cline’s scheme.

Not to be deterred (and suddenly having a dozen or so life-sized fiberglass dinosaurs that he needed to so something with), Cline moved his dinosaurs to a forested tract of land adjacent to his Professor Cline’s Haunted Monster Museum & Dark Maze, giving visitors two attractions for one admission price. But he went much further than just plopping a bunch of recreated dinosaurs under the trees and behind the bushes. He imagined a whole alternate history scenario for his creations to romp in, combining his love of dinosaurs, his fondness for the old Ray Harryhausen movie The Valley of Gwangi (also a childhood favorite of mine; my best friends and I stayed up late to watch it during my eighth birthday party), and the regional fascination with the Civil War. He called his new attraction Dinosaur Kingdom.

“(V)isitors are asked to imagine themselves in 1863. A family of Virginia paleontologists has accidentally dug a mine shaft into a hidden valley of living dinosaurs. Unfortunately, the Union Army has tagged along, hoping to kidnap the big lizards and use them as ‘weapons of mass destruction’ against the South. What you see along the path of Dinosaur Kingdom is a series of tableaus depicting the aftermath of this ill-advised military strategy. As you enter, a lunging, bellowing T-Rex head lets you know that the dinosaurs are mad — and they only get madder. A big snake has eaten one Yankee, and is about to eat another. An Allosaurus grabs a bluecoat off of his rearing horse while a second soldier futilely tries to lasso the big lizard. Another Yankee crawls up a tree with a stolen egg while the mom dinosaur batters it down.”

Perhaps Cline’s most famous, or infamous, creation arrived the following year, landing on the Natural Bridge landscape overnight, once more on Cline’s favorite day of the year, April Fools’ Day. “‘About 15 years ago I walked into a place called Insulated Business Systems where they make these huge 16-foot-tall blocks (of Styrofoam),’ Mark tells us. ‘As soon as I saw them I immediately thought of the idea: “Foamhenge.” It took a while for the opportunity to present itself, of course.’ … It is, Mark points out, the only American Stonehenge that really is an exact replica of the time-worn original. ‘I went to great pains to shape each “stone” to its original shape,’ he tells us, fact-checking his designs and measurements with the man who gives tours of Stonehenge in England. Mark has even consulted a local ‘psychic detective’ named Tom who has advised him on how to position Foamhenge so that it is astronomically correct.”

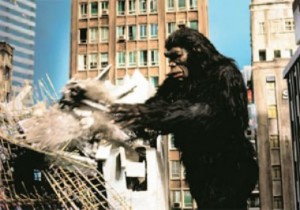

Cline’s creations have spread beyond the immediate vicinity of the Natural Bridge monument and park. A few miles to the north, near the access road to another local attraction, the Virginia Safari Park, Cline installed a 14 foot-tall statue of King Kong in the parking lot of the Pink Cadillac Diner. He explains this was actually a protest against the local government’s having forced him to take down one of his signs: “I placed it there three years ago after the county made me take down one of my signs that they said was illegal… Since it’s too much of a challenge to regulate ‘art,’ they left King Kong alone. Now many of the supervisors wished they had left my sign alone.”

Cline’s unfortunate history with fire nearly repeated itself shortly before September 11, 2011, the tenth anniversary of the 9/11 terrorist attack. A businessman in Waynesboro, Virginia, who had been a high school classmate of Cline’s, arranged for Cline to create a fiberglass memorial to the Twin Towers. However, while the memorial was being installed, a support cable touched a live power line, creating a shower of sparks and a major power outage in Waynesboro. Cline’s creation almost burning down before it was unveiled.

Far worse was yet to come, however. 2012 began auspiciously for Cline; the struggling Taubman Museum of Art in Roanoke, Virginia decided to host an exhibition of Cline’s weirdest figures in February, advertising it as a major retrospective of American folk art. The event was featured in an article in the Wall Street Journal. Investors flew him on a private jet to New Jersey to have him consult on a big job; other art museums contacted him, as well as the producers of a reality TV show. However, just two months later, the centerpieces of his entertainment empire, his Haunted Monster Museum and Dinosaur Kingdom, suffered a devastating fire eerily similar to the fire which had destroyed the Enchanted Castle eleven years earlier.

“A mid-April blaze demolished the Victorian-era mansion that served as the Haunted Monster Museum as well as the centerpiece of a bizzaro place called Dinosaur World where dinos would gobble Union soldiers and where brave visitors could also hunt Bigfoot with a ‘redneck.’ … Although the fiberglass dinos in the woods outside were saved, the Monster Museum was incinerated. The mechanical rats, the ‘Elvis-stein’ monster, and the mighty fiberglass python that seemed to slither in and out of the second-story gable windows all went up in flames late on the afternoon of April 16. … Like the rest of us, Cline says he’s now trying to face the prospect of a summer without his Monster Museum. He’s seen an uptick in contract work, like the 13 men’s room sinks he recently built for the Broadway revival of How to Succeed in Business without Really Trying. A couple of reality show producers have made inquiries about following him around. Cline veers between ‘pissed off’ anger at an unknown arsonist and the peace of knowing that nobody was killed or injured in the fire.”

Cline’s website, Monstersanddinosaurs.com, has announced plans to reopen the Haunted Monster Museum and/or Dinosaur Kingdom “sometime in 2013.” Until that happy day arrives, fans of Cline’s work can still visit Foamhenge, accompany Mark and his wife Sherry on Lexington, Virginia’s Ghost Tour, or see the artist at work at his Enchanted Castle Studio on the grounds of his former attraction, the Enchanted Castle, the remnants of which can still be viewed from U.S. Highway 11. Cline’s work is also on prominent display along the main commercial drag of Virginia Beach, where his creations are a large part of the appeal of such tourist draws as Nightmare Mansion, the 3-D Fun House and Mirror Maze, and Cap’n Cline’s Pirate Ghost Ride (which replaced a long-running funhouse attraction called Professor Cline’s Time Machine).

And, of course, Mark Cline’s dinosaurs can still be enjoyed at the very place where all of his dreams got their start, White Post, Virginia’s Dinosaur Land (I did a three-part post on my family’s trip to Dinosaur Land, chock full of terrific photos of Cline’s dinos).