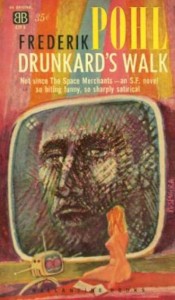

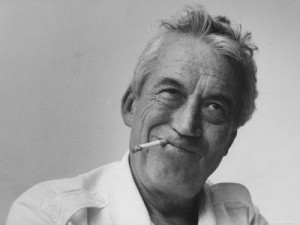

Drunkard’s Walk

Frederik Pohl

Original Edition: Ballantine Books, 1960 (following serialization in Galaxy Science Fiction)

Most Recent Edition: Ballantine Books, 1973

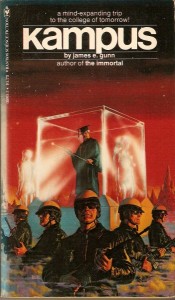

Kampus

James Gunn

Original Edition: Bantam Books, 1977

Most Recent Edition: Kindle, 2010

Over the past thirty years, the level of interest in science fiction shown by academia has grown at least tenfold, with hundreds of campuses now offering courses on science fiction as literature or science fiction as a prominent branch of popular culture, and a handful of universities offering full degree programs in science fiction. However, the level of interest running in the opposite direction – the interest of science fiction authors in extrapolating the future of academia—has been rather lower. Few major works of science fiction have taken up potential future developments in higher education as their primary subject. I find this to be a bit surprising, given the not insubstantial contingent of science fiction writers who currently earn the majority or a sizable portion of their income serving as university faculty.

Examining potential futures for academia and the university system is a timely endeavor. America’s university system, long considered one of the crown jewels of the nation’s economic and social infrastructure, now finds itself at the confluence of powerful societal trends, technological, economic, and political in nature, which will almost certainly reshape much of that system within a decade or two into forms which may be drastically different from the norms we as a society have become accustomed to since the Second World War and the granting of the G.I. Bill educational benefits to veterans.

Much has been written in recent years about the suspected inflation of a higher education bubble which mimics in many of its aspects the housing bubble whose bursting brought on the 2008 recession. Since 1985, the cost of college tuition and fees has increased nearly 500%, versus a 115% increase in overall consumer prices. Student loans, a majority of which are backed by the federal government, are non-dischargeable in bankruptcy, and many students find themselves graduating from a four-year program of liberal arts study with the equivalent of a home mortgage (debt loads for many graduates of private universities approach a quarter of a million dollars, with the graduates of public universities not far behind). Even worse off than the graduates are the more numerous drop-outs; they are saddled with sizable debt burdens but have no credential in hand to assist them in finding work which will allow them to repay their loans. Many observers feel that current trends in higher education are unsustainable and that a crisis, or a combination of crises, will force the system into radical change.

What might those changes look like? Two prominent science fiction authors, Frederik Pohl and James Gunn, have painted portraits of potential futures for the higher education system. Their novels were published seventeen years apart – Pohl’s Drunkard’s Walk in 1960 and Gunn’s Kampus in 1977. Giving credence to the truism that science fiction is more about the present than it is about the future, each book strongly reflects the academic milieu which was prevalent during the period of its writing: for Pohl’s, the Sputnik Era, fear-driven lionization of the hard sciences and the concurrent dedication of significant government funding to basic research efforts at the universities; and for Gunn’s, the student radicalism and participatory democracy and identity group power movements of the mid-to-late 1960s and early 1970s, which, by 1977, had mostly retreated from large-scale public protests to their bases on university campuses.

Drunkard’s Walk was originally serialized in a shorter form in Galaxy Science Fiction in 1960. Pohl’s novel has the feel of a typical late-1950s Galaxy story: a surface urbanity and wit, many clever turns of plot, and characterization about as deep as that found in a Twilight Zone episode of the same era. The novel-length Drunkard’s Walk, although not a long book, suffers some from excess padding glued to its flanks during the effort to expand it from a novella to a novel; many of the chapters told from the vantage point of a supporting character, Master Carl, feel tacked on and unnecessary. The primary problem faced by the protagonist, Master Cornut, a mathematics professor at an unnamed University, is both original and compelling—during periods of partial consciousness, such as when he is on the verge of falling asleep, has just woken up, or is distracted by the progress of one of his own lectures, Cornut is plagued by an autonomous compulsion to commit suicide, despite being a happy, privileged, and well-adjusted individual. He is forced to rely upon the watchfulness of those who live adjacent to his on-campus living quarters, initially students and later his student wife, to keep himself from slitting his own throat or hurling himself over the railing of his apartment’s balcony. Where the plot ultimately heads is less fresh, at least from the present vantage point of an additional half-century of science fiction stories and films, involving as it does the trope of a conspiracy of secret immortals who seek to wipe out potential rivals before those rivals can realize their own power.

For today’s reader, the primary draw of Drunkard’s Walk may be its setting, the University where Master Cornut teaches. Pohl paints the University as a refuge from the overcrowded, tumultuous outside world, where a sizable portion of the American lower middle class is forced to live on “texases,” off-shore platforms originally constructed as early-warning radar installations, which are now used for dirty jobs such as manufacturing and raw materials processing (each texas produces its own power from the wave energy that crashes continuously against its support legs). The book’s most accurate extrapolation is Pohl’s envisioning of distance learning; each professor’s lectures are taped and broadcast, reaching audiences of millions, those who either aspire to degrees of higher learning or who desire access to knowledge:

“Cornut had more than a hundred live watchers—the cream; the chosen ones who were allowed to attend University in person—but his viewers altogether numbered three million. …

“For education was something very precious indeed.

“The thirty thousand at the University were the lucky ones; they had passed the tests, stiffer every year. Not one out of a thousand passed those tests; it wasn’t only a matter of intelligence, it was a matter of having the talents that could make a University education fruitful—in terms of society. For the world had to work. The world was too big to be idle. The land that had fed three billion people now had to feed twelve billion.

“Cornut’s television audience could, if it wished, take tests and accumulate credits. … Almost always the credits led nowhere. But to those trapped in dreary production or drearier caretaker jobs for society, the hope was important. There was a young man named Max Steck, for example, who had already made a small contribution to the theory of normed rings. It was not enough. Sticky Dick said he would not justify a career in mathematics. He was trapped as a sexwriter, for Sticky Dick’s analyzers had found him prurient-minded and creative. There were thousands of Max Stecks.

“Then there was Charles Bingham. He was a reactor hand at the 14th Street generating plant. Mathematics might help him, in time, become a supervising engineer. It also might not—the candidates for that job were lined up fifty deep. But there were half a million Charles Binghams. …

“These, the millions of them, were the invisible audience who watched Master Cornut’s image on a cathode screen.”

Pohl places the University’s professors, or Masters, at the top of his social pecking order. Masters may take advantage of a sort of droit de seigneur regarding the University’s students. Conjugal relations between professors and students are encouraged, being viewed as beneficial to each, and what are called “term marriages” are common, which may last (presumably on the Master’s prerogative) as briefly as a few weeks. There is a strict separation between Town and Gown, with the latter acting in many ways as a sort of hereditary landed aristocracy, but one which sometimes opts to absorb very talented members of the former into its ranks (as scholarship students).

That strict separation between Town and Gown is mirrored in James Gunn’s Kampus, but the relative status of the two is nearly inverted. Gunn, born in 1923 (four years after Frederik Pohl), is a professor emeritus at the University of Kansas and the director of its Center for the Study of Science Fiction. Following an estimable career as a science fiction author and anthologist, he became one of the pioneering academicians to teach science fiction. He was a personal witness (from the faculty side) to the campus upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s, and the first third of Kampus takes place on the University of Kansas campus at some point early in the twenty-first century. A series of social upheavals has caused state governments to essentially surrender their university campuses to student control. Walled off from the surrounding communities, the campuses act as holding pens for the revolutionary young adult offspring of the middle and upper middle classes, who are free to act out their anarchistic, communitarian, or socialist fantasies within the walls. Symbols of authority are still present, in the form of Kampuskops, but these are more actors in revolutionary theater than agents of bureaucratic control, present mainly to give the student activists and revolutionaries someone to act against.

In contrast to the University portrayed in Drunkard’s Walk, within the universities of Kampus the professors have virtually no social status at all. In the absence of state financial support, they are reduced to competing with one another for paying students, each trying to outdo the others with promises of lurid classroom content, skills to be gained in manipulating peers, and drug experimentation. Professors must be transported to and from their classrooms in armored cars, since campuses are rife with plots to kidnap them and demand various forms of ransom. Students live in self-righteous squalor, mostly unaware that small cadres of student leaders pull their strings and benefit from unlimited sexual partners and access to endless supplies of psychoactive drugs. These cadres keep the student populations entertained and distracted with violent demonstrations on campus and destructive raids into the surrounding communities, which hate and fear the students.

Very little in the way of active learning takes place. Students are supplied with their degree parchments on the first day of their matriculation; they are also issued learning pills that encode the peptides of popular professors and allow some forms of knowledge to be effortlessly passed on. The novel’s protagonist, Tom Gavin, enrolls in a philosophy course offered by one of the few traditional professors remaining on campus. He becomes so enthralled with the Socratic experience that he plots to kidnap the Professor in order to extract peptides from his blood and create new learning pills that will allow Tom to internalize all of his knowledge. The kidnapping leads to a regrettable denouement, but before it does, the Professor has an opportunity to deliver a potted history of the devolution of higher education:

“‘Here I stand,’ the Professor said, ‘tearing my breast to bleeding shreds like the fabled pelican to feed you ungrateful chicks, in a place where learning has fled, where man has retreated from intellectual activity to ritual. I have lived through it all. I have seen the University retreat from educational standards and academic freedom through autonomous black-studies curricula, general studies, and student participation in University governance to total lack of concern for objective educational criteria and to the abandonment of the campus by serious scholars and scientists. Where has learning fled?

“‘How many of you know that when you matriculate in this University you are automatically awarded a degree? Of course, most of you stay around to play in the sandbox you call a university, and a few of you, to seek out an education. Where has learning fled?

“‘The practice of students hiring and paying their own teachers goes back to the first university, at Bologna, founded in the eleventh century, but it soon was recognized as the pure bologna it was. Students do not know what they need to know; if they knew, they would not need teachers. Well, the Dark Ages returned as public support for higher education gradually was withdrawn from campuses, enrollments began declining, and faculty became increasingly dependent upon student fees; the ancient pattern of student control and student hiring, firing, and payment of faculty reestablished itself. The result, you see around you–not teachers but charlatans, pimps pandering to student lusts in the name of relevance. Relevance–that’s what we call it when our prejudices are reinforced. A basic principle of education is that you cannot learn anything from someone with whom you agree.'”

Student rivalries and the machinations of StudEx, the student leadership executive board, force Tom to leave the University of Kansas once he has become a threat to StudEx’s power. He sets out across the country, Candide-like, confident in his revolutionary-socialist-egalitarian ideals, to see for himself the semi-legendary University of California at Berkeley, the font of the student revolutionary movement. He falls in with a young female companion of a much more practical bent, an orphan who graduated from the school of hard knocks and who has no patience for Tom’s high-flown ideals, but who loves him and tries (not always successfully) to protect him from the consequences of his own naiveté. On the course of their travels, we readers discover “where the learning has gone:” practical, technical instruction has migrated to a system of highly automated community colleges, matriculating a mostly lower class and working class student body who are motivated to achieve wealth, not social equality, and theoretical and applied research have left the universities for secluded mountain havens funded by philanthropic billionaires.

Kampus is a more ambitious novel than Drunkard’s Walk. Its characters, at least the protagonists, are drawn with greater psychological depth than those of the earlier book. Pohl’s prose is sturdy and workmanlike, never flashy or evocative, whereas Gunn’s frequently achieves real beauty. If Kampus can be said to have a significant flaw, it is that too many of its well delineated and highly entertaining episodes teach the same lesson to Tom Gavin, who, until the book’s end, seems stubbornly resistant to learning what is endlessly rubbed in his face – that beautiful ideals may often hide venal motivations, and that violence, rape, and theft committed in the stated pursuit of a more egalitarian society are still violence, rape, and theft. Many readers will be tempted to give up on Tom halfway through the novel, but the charm and vividness of Gunn’s prose, plus his deft hand at keeping his plot moving, will keep them on board through the end. Some reviewers have remarked that the scenarios extrapolated in Kampus are dated and were dated even when the book was written in 1977. However, the recent saga of Occupy Wall Street and the other Occupy movements around the country makes many of the events and actors of Kampus feel very current.

Which of the novels is more relevant to the situation faced by higher education today? Pohl was certainly on to something with his description of the ubiquity of distance learning, and Gunn made prescient points concerning the growing divide between teaching and research and the likelihood that, should colleges and universities abandon the teaching of the practical arts, other institutions (such as the Internet) will rise to fill the gap. Interestingly, whereas the earlier book portrayed the professors as the top of the heap and the latter book did the same for the students, in actuality a third group, hardly mentioned by either novel, appears to have been the biggest beneficiary of the enormous growths in university budgets over the past thirty years – the administrators. As the numbers of tenured faculty have plummeted at most colleges and universities, replaced by adjunct or part-time instructors, the numbers of administrators and managers, in new areas like environmental compliance and diversity observance, have skyrocketed, and many of those administrators enjoy salaries and power well beyond those extended to professors.

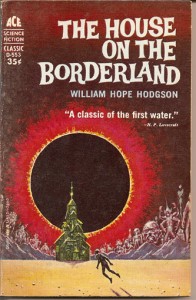

My own recent novel No Direction Home posits a third possible future for higher education. In the mid-twenty-first century, much of the middle class has abandoned the old American Dream of homeownership and college education. A large portion of the population has taken up a nomadic existence, living as gypsies in their electric cars and moving between short-term jobs, flowing wherever the demand for labor arises. Most states, strapped for cash, have closed their public universities. College education has reverted to what it was prior to the Second World War – a status good, a privilege available primarily to the wealthy. Most gypsies obtain what training and education they need for their short-term jobs from the Internet setups built into their vehicles, and they are guided in their courses of learning by one-time professors, laid off from public universities, who now accompany the gypsy crews on their travels. Those gypsies who wish to pursue non-vocational learning attend roadside seminars and salons offered by the professors, after-work perks provided by the organizers of the crews.

So the future I’ve envisioned for higher education combines elements of Frederik Pohl’s extrapolations (universities limited to the wealthy and/or privileged; widespread distance learning) with those of James Gunn’s (teachers as migrant free agents offering their services to students; practical training provided in electronic form). For what it is worth, I wrote my novel prior to reading either Drunkard’s Walk or Kampus. The confluence between my book and theirs proves to me yet again that science fiction is a conversation carried out over decades, with effective exchanges taking place even in the absence of direct influence or knowledge; a form of telepathy between writers, perhaps, or at least of the convergent modes of thinking that arise from the practice of science fiction.

In a recursive hall of mirrors, professors who are science fiction writers may teach science fiction books about the future of academia… wherein science fiction writers teach books extrapolating the future of academia…