As I’ve mentioned many times on this blog before, one of the great pleasures of raising children is getting to enjoy many of one’s childhood enthusiasms all over again, this time experiencing the “doubled vision” of seeing them through one’s own, matured eyes and the less jaded eyes of one’s kids.

With this in mind, I’ve been having a grand ol’ time renting vintage monster and kaiju movies from Netflix and watching them with my boys. Judah, my youngest, is my most enthusiastic co-conspirator, but both Asher and Levi will usually plop down on the bed with the two of us to watch whatever “monstrous” piece of celluloid Dad has selected for the evening. A bonus of this is that I’m actually getting to see lots of films that I only read about as a kid – a number of Japanese horror films, for example, had only limited exposure in the U.S. and weren’t part of the popular TV movie packages, shown by independent TV stations, that I relied upon during my childhood viewings. I don’t recall ever seeing Atragon, The Mysterians, Frankenstein Conquers the World/Frankenstein vs. Baragon, Dagora, the Space Monster, Gappa, the Triphibian Monster, Yongary, Monster from the Deep, or Varan the Unbelievable as a kid. However, now, thanks to the ubiquity of DVD players and the hunger of services such as Netflix for product, all of these movies are currently available, and I’ve either recently watched them with my boys or have stuck them in my order queue.

(Special bonus for you Toho Studios fans – here’s a marvelously informative year-by-year listing of all the films Toho has made, from their founding in 1935 to 2012.)

Over the next few days, I’ll be writing a bit about giant monster movies I’ve recently shared with my kids, listing them in descending order of quality and entertainment value (mind you, these two aspects do NOT necessarily track in parallel, as any fan of 1950s monster movies and Japanese kaiju films will attest).

At the top of my list are several of what must be considered Toho’s B-list of horror and science fiction films (their A-list, or most popular and best-remembered horror and SF movies, are the Godzilla series and their most closely-related offshoots, Mothra and Rodan). Toho was a very prolific company in the middle decades of the twentieth century, producing films in a wide variety of genres – gangster pictures; war films; romance movies; and classics of world cinema such as Seven Samurai (1954) and The Throne of Blood (1957).

Beginning with Godzilla, King of the Monsters in 1954, the studio delved into the realms of science fiction and horror, producing at least one movie per year in these genres over the following decade and a half:

Godzilla Raids Again and Half Human in 1955;

Rodan (in color!) in 1956;

The Mysterians (also in color) in 1957;

Varan the Unbelievable and The H-Man in 1958;

Battle in Outer Space in 1959;

The Human Vapor in 1960;

Mothra in 1961;

King Kong vs. Godzilla and Gorath in 1962;

Atragon and Matango/Attack of the Mushroom People in 1963;

Mothra vs. Godzilla/Godzilla vs. The Thing, Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster, and Dagora, the Space Monster in 1964;

Invasion of the Astro-Monster/Godzilla vs. Monster Zero and Frankenstein vs. Baragon/Frankenstein Conquers the World in 1965;

Ebirah, Horror of the Deep/Godzilla vs. the Sea Monster and The War of the Gargantuas in 1966;

Son of Godzilla and King Kong Escapes in 1967;

Destroy All Monsters in 1968, arguably the pinnacle of the original Toho kaiju cycle, starring, as it did, virtually all the monsters they had fielded in the prior decade;

and All Monsters Attack/Godzilla’s Revenge in 1969, to many fans, the nadir of the original kaiju cycle, making heavy use of footage already seen in Son of Godzilla and Godzilla vs. the Sea Monster and centering the story on a young boy’s wish fulfillment daydreams (which works better for young viewers than it does for kaiju fans in their twenties or thirties or, Lord help me, forties).

The studio continued pumping out at least one monster picture each year, until they took a break following 1975’s Terror of Mechagodzilla. With the exception of 1977’s The War in Space, which was released direct-to-VHS in the U.S., Toho did not return to the horror or science fiction genres until 1984’s The Return of Godzilla (released the following year in the U.S. as Godzilla 1985, which I recall dragging my then-girlfriend Leslie to a cheapie theater in New Orleans to see).

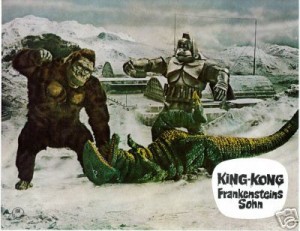

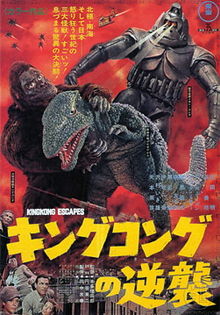

The best (or the most entertaining) of Toho’s B-list that I recently watched was – surprise, surprise! — King Kong Escapes. I say “surprising” because I was more than a little amazed by just how much I enjoyed this film. I’ve gone through three stages, it seems, regarding Toho’s two King Kong films. King Kong vs. Godzilla was one of the very first kaiju pictures I ever saw; my parents let me stay up “late” as a five-year-old to watch it on TV. For years thereafter, I claimed it as my favorite movie of all time. However, when I entered junior high school, I began doing some serious study of stop-motion animation, with the hope of learning to become an animator myself; I studied the work of Willis O’Brien, Ray Harryhausen, and Jim Danforth and even wrote a thesis paper in eighth grade on the history of stop-motion animation, following up the next year with an attempt to make my own stop-motion fantasy film. You might say I became a “stop-motion snob,” staring down my nose at all inferior forms of special effects, particularly the use of lizards with glued-on horns and fins to portray dinosaurs, and men in suits to portray various giant monsters – including King Kong. Thus, I had to disavow my earlier, “childish” enthusiasm for King Kong vs. Godzilla (and admittedly, the King Kong outfit used in that film was not one of Toho’s better designs). Until just recently, I never had the opportunity to see Toho’s follow-up, their second and last King Kong effort, King Kong Escapes, but I tarred it with the same brush, assuming it was another attempt to profit off Willis O’Brien’s legacy while dishonoring his technical and artistic accomplishments.

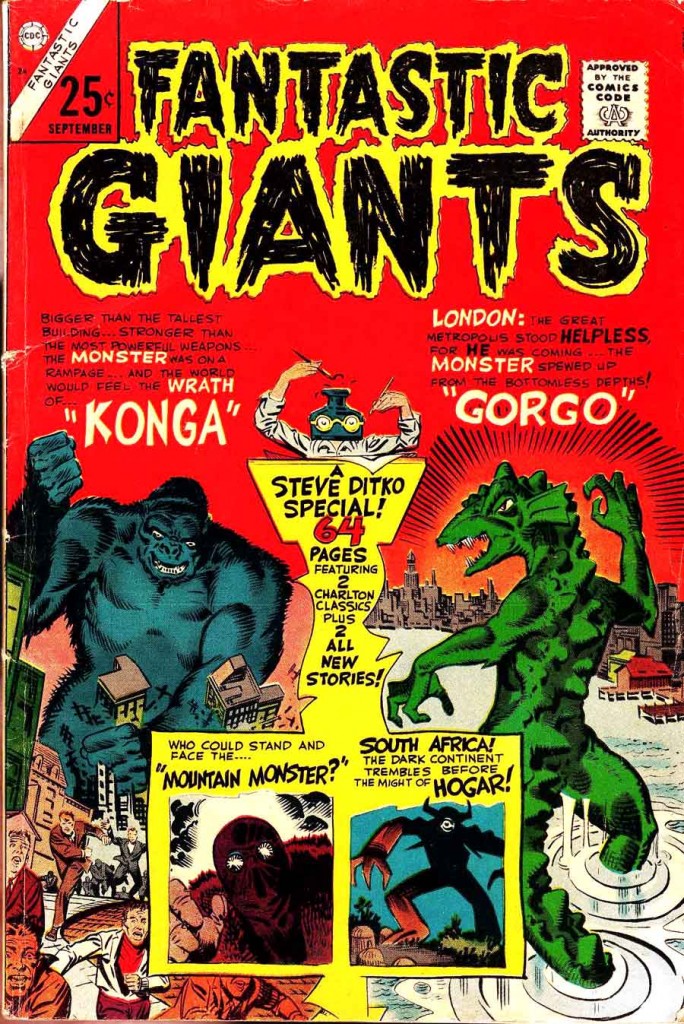

Hey, one’s perspective changes as one gets older (particularly after one has kids). Now I’m able to look at these Toho second stringers with the eyes of a little boy again, and in that light, King Kong Escapes is fantastically entertaining. It helps that Toho did a much better job with the Kong suit the second time around; it looks much more gorilla-like than the suit used in King Kong vs. Godzilla (the arms are longer and the legs are proportionately shorter), and it even bears a passable resemblance to the original, 1933 King Kong in design. Also, just as there is splendid stop-motion animation (Mighty Joe Young) and barely passable stop-motion animation (Flesh Gordon), so are there gradations in quality of monster suit acting, from very effective (Godzilla vs. the Thing) to absolutely abysmal (Konga — see my review here). I thought the monster suit acting in King Kong Escapes was quite good (Haruo Nakajima plays Kong, and Yu Sekida plays dual roles as Mechani-Kong and Gorosaurus, who later reappears in Destroy All Monsters). All three kaiju have distinctive personalities, entirely portrayed through the actors’ movements.

But what really makes the movie so much fun are the villains. Eisei Amomoto as Dr. Hu (sometimes spelled Dr. Who) and Mie Hama as Madame Piranha enthusiastically chew the scenery, and they manage to make it look like it tastes delicious. The plot doesn’t make a whole lot of sense (oftentimes, the plots of Toho’s monster and science fiction movies are either slender as sheets of paper or lose much in the translation to English). Dr. Hu wants to excavate a large quantity of a radioactive miracle metal from deep beneath the Arctic ice so he can sell it to the leadership of a rogue nation, represented by Madame Piranha. To get at the metal, he builds a gigantic robot gorilla(?), but unfortunately for his plans, its mechanical innards are set out of whack by radioactivity. Not allowing this little setback to stop him, he then arranges for the kidnapping and brainwashing of King Kong from Kong’s island, intending to use a real giant gorilla to dig out the precious metal where the robot giant gorilla had failed. However, King Kong escapes, the villain’s plans go awry, real Kong fights robot Kong, yada, yada, yada… Along the way, Dr. Hu twirls his mustache and Madame Piranha seduces the hero and we all have a great time. The Dr. Hu/Madame Piranha pair rate up there with my favorite of the Toho horror/SF villains – the Controller of Planet X (Yoshio Tsuchiya) from Invasion of the Astro-Monster, who combines a really cool alien uniform with some of the niftiest pinky choreography ever seen on film (only rivaled, perhaps, by Marlee Matlin’s sign language in Children of a Lesser God).

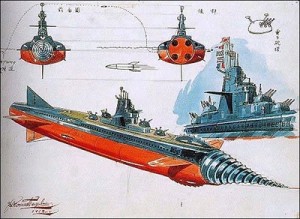

Next up on our list of very enjoyable Toho B-movies is Atragon from 1963. Atragon barely qualifies as a kaiju film; the only giant monster present is Manda, the dragon/serpent god of the subterranean Mu people. Manda plays a fairly minor role in the movie, but he does come back to appear again in Destroy All Monsters and puts in a cameo appearance in Godzilla’s Revenge. His main purpose in Atragon is to provide opposition for the movie’s titular super-submarine (which manages to subdue the giant dragon/serpent without much fuss, via a “freezing ray” which, in strange contradiction of the laws of thermodynamics, can be used underwater without freezing any seawater but which nonetheless manages to freeze Manda in ice!).

Manda is not the main attraction of Atragon, by any means. The film’s star turns are provided by veteran Toho actor Jun Tazaki, who portrays Captain Hachiro Jinguji, last active officer of the Imperial Japanese Navy, and by Eiji Tsuburaya and Takeo Kita, respectively the film’s Visual Effects Director and Production Designer. Jun Tazaki brings massive screen presence to any role and will be familiar to any fan of kaiju movies from his turns in such films as Gorath, King Kong vs. Godzilla, Mothra vs. Godzilla, Dagora, the Space Monster, Frankenstein vs. Baragon, Invasion of the Astro-Monster, Godzilla vs. the Sea Monster, The War of the Gargantuas, and Destroy All Monsters. (His final film role prior to his death in 1985 was in Akira Kurosawa’s epic retelling of the story of King Lear, Ran, set in feudal Japan.) Tazaki was given an unusually meaty character to play in Atragon (unusually meaty for a kaiju picture, that is, which typically features underdeveloped human characters) – Captain Hachiro Jinguji of the Imperial Japanese Navy, who escaped capture at the end of the Second World War and never accepted Japan’s defeat. He stole away with his advanced submarine and crew and, after losing his sub to raiders from the Mu people, settled on an isolated atoll, created an underground factory, and spent the next eighteen years building a new, super-advanced submarine with which to win back Japan’s martial honor. After the Mu people attack Japan and threaten to conquer the entire surface world, Captain Jinguji’s daughter, whom he had not seen since the last days of the war, when she’d been a little girl, finds him and begs him to use his super-sub against the Mu, as it is the only weapon the Mu have reason to fear. The fiercely patriotic Jinguji balks at first, refusing to use the Atragon for any purpose other than revenging Japan upon America. But he is eventually won over and proceeds to deliver a spectacular ass-whupping to the Mu, destroying their best submarines, demolishing their power source, defeating their giant serpent god, and even capturing their queen, who opts, at the very end, to share the fiery demise of her people.

Just as good as Jun Tazaki’s performance is the design of the super-sub, Atragon. What’s not to love about a giant flying submarine? My youngest, Judah, was entranced. As well he should be – the Atragon is every young boy’s dream come true, with its sleek design, its gun turrets, its eye-catching color scheme, and its freeze-ray in the nose. Judah spent the week following seeing this movie drawing picture after picture of flying submarines. Of course, he has been begging me for a toy Atragon. And, yes, such a thing is available!

Next: More of Toho’s Second String!

Frankenstein Conquers the World/Frankenstein vs. Baragon

The Mysterians

Dagora, the Space Monster