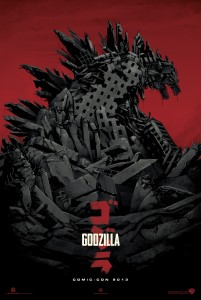

Note: This is an article I originally published in July, 2013. I haven’t yet seen the new American Godzilla, so this isn’t a review of that. Rather, this is a look back at the most recent reboot of Godzilla, Japanese-style, and a comparison with the most recent reboot of one of Godzilla’s screen rivals, Gamera.

___________________________________________________________________________

With little-known director Gareth Edwards currently working on an American reboot of Godzilla, scheduled for release during the Big G’s sixtieth anniversary in 2014, I thought it would be a good time to take a look back at the last time movie-makers gave rebooting classic kaiju characters a shot. The most recent two efforts were Godzilla: Final Wars (2004) and Gamera the Brave (2006). I recently had an opportunity to view the two films almost back to back, in order to best compare and contrast their differing approaches to renewing the appeal of long-lived kaiju stars.

Godzilla: Final Wars represented Toho Studio’s fiftieth anniversary celebration of their most famous creation. It was their 28th Godzilla film and the sixth in the Millennium series (the character’s earlier two series are known as the Showa series and the Heisei series). They clearly meant to “pull out all the stops” with this film, stuffing it full of monsters from earlier movies (many of which had not been seen on the big screen in twenty-five or thirty years), cameo appearances from veteran Godzilla actors, and many hat tips to plot elements from earlier films (the alien Xilians have a good bit in common with the aliens from Planet X in Godzilla vs. Monster Zero). In many ways, it can be seen as a remake of Toho’s fondly remembered Destroy All Monsters (1968), which featured eleven of Toho’s kaiju stable.

One of the oddest elements of the film is how little of it is dedicated to its supposed star, Godzilla. In common with nearly all the films of the Heisei and Millennium series, Godzilla is portrayed with minimal personality, little more than a very bad-ass radioactive dinosaur with a great big chip on its shoulder. Thus, the screenwriters felt compelled to fill up the majority of the movie with plot elements centering on the human (or mutant) characters. The first half of the movie comes off as a Japanese version of the X-Men film series. It focuses almost entirely on two rival mutant soldiers in the Earth Defense Force’s M-Unit. The two mutants, Shinichi and Katsunori, are both friends and rivals, and they vie for the affections of a molecular biologist, Miyuki, who is recruited by the United Nations to study a mummified space monster (which turns out to be Gigan). Another standout character is Douglas Gordon (portrayed by American mixed martial artist and professional wrestler Don Frye), the captain of the EDF’s attack submarine, the Gotengo (itself a retread of the submarine from 1963’s Atragon). The Gotengo, with Gordon aboard as a young cadet, had trapped Godzilla in Antarctic ice forty years prior to the future in which Final Wars is set. In a weird costuming choice (which somehow works for me), Gordon, who is presumably an American working for the United Nations, dresses like a World War Two-era Russian commissar.

No one can complain that they skimped on the monsters!

The biggest draw of the film is the huge number of giant monsters from earlier Godzilla movies which it drew out of retirement. Final Wars tops Destroy All Monsters’ tally by featuring fourteen kaiju (or twenty-one, if you include seven kaiju who make brief appearances via stock footage). The all-star line-up includes Godzilla (last seen in 2003’s Godzilla: Tokyo S.O.S.), Manda (most recently seen in Destroy All Monsters back in 1968), Minilla (this version of the Son of Godzilla hadn’t been on screen since 1969’s Godzilla’s Revenge), Rodan (as Radon, he’d last appeared in 1993’s Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla 2), Anguirus (most recently seen in 1974’s Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla), King Caesar (his only prior appearance was in the 1974 Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla), Mothra (most recently seen in 2003’s Godzilla: Tokyo S.O.S.), Monster X/Keizer Ghidorah (Ghidorah, a Toho staple, had last appeared in Godzilla, Mothra, and King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack in 2001), Gigan (not seen since 1972’s Godzilla vs. Gigan), Hedorah (his only star turn had come in 1971’s Godzilla vs. the Smog Monster), Ebirah (last seen, in stock footage taken from 1967’s Gozilla vs. the Sea Monster, in Godzilla’s Revenge in 1969), Zilla (the American Godzilla, whose only appearance came in 1998’s Godzilla), Kumonga and Kamacuras (both previously seen in Godzilla’s Revenge). Other classic kaiju also make brief appearances via stock footage, including Varan (last seen in Destroy All Monsters after starring in Varan the Unbelievable in 1958), Baragon (most recently seen in 2001 in Giant Monsters All-Out Attack), Gezora (Space Amoeba, 1970), Gaira (The War of the Gargantuas, 1966), Mechagodzilla (most recently seen in Godzilla: Tokyo S.O.S. in 2003), Megaguirus (Godzilla vs. Megaguirus, 2000), and Titanosaurus (Terror of Mechagodzilla, 1975).

What do you get when you cross a kaiju with a Swiss Army Knife?

Unfortunately, having to divide screen time between so many monsters leaves precious little time for any individual monster to shine, especially given that much of the first half of the movie is given over to interactions between the human, mutant, and space alien characters. For example, I would’ve loved to see more of a rematch between Hedorah, the Smog Monster, and Godzilla, but their battle takes up less than ten seconds on screen, Godzilla batting him aside as though he were a tomato can. (By way of contrast, in their first encounter, back in 1971’s Godzilla vs. the Smog Monster, retroactively written out of existence in the Millennium series, the Big G took an entire movie to figure out how to put Hedorah down for the count; the Smog Monster was one of those horrors who got “killed” multiple times but kept rising from apparent defeat.)

Part of the conceit of the films of the Millennium series is that none of them follow the earlier movies in the series; the only precursor each film has is the original 1954 Godzilla, King of the Monsters. Thus, each Millennium movie represents a reboot of almost everything that came before it. However, over his then fifty-year history in films, Godzilla had enjoyed long, even complex relationships with a number of other kaiju. Ghidorah was the George Foreman to Godzilla’s Mohammed Ali, having fought Godzilla nearly ten times before. Godzilla also boasted some allies of long-standing. Rodan had assisted him in Godzilla vs. Monster Zero and Destroy All Monsters before battling him (as Radon or Fire Rodan) in Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla 2. Anguiras started out as a foe in the very first Godzilla sequel, Godzilla Raids Again, and then became one of Godzilla’s most indefatigable allies in Destroy All Monsters and the original Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla. Godzilla’s most interesting long-term relationship could be said to be the one he shared with Mothra. They had started off as antagonists (in 1964’s Godzilla vs. Mothra), gone on to be allies in multiple adventures (in Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster, Godzilla vs. Monster Zero, Godzilla vs. the Sea Monster, and Destroy All Monsters), become enemies again (in Godzilla, Mothra, and King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack), and finally allies once more (in Godzilla: Tokyo S.O.S. and Godzilla: Final Wars. Yet because of the set-up of Final Wars and all the earlier films in the Millennium series, the screenwriters had to pretend that the clashes in Final Wars (all the other monsters, with the exceptions of Manda and Mothra, were under the mental control of the Xilians) represented the very first time that Godzilla was encountering his fellow kaiju.

I think this represented a major lost opportunity for the makers of Final Wars. For me, at least, a good bit of the attraction and charm of the later films in the original Showa series, from Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster through Terror of Mechagodzilla, comes from the interactions between Godzilla and his fellow monsters. In the Showa series, the last film in which Godzilla is a pure heavy is Godzilla vs. Mothra; beyond that film, Godzilla generally serves as a protector of Japan or at least a somewhat benevolent force, allied to an extent with the human heroes. Although his antics could sometimes be silly (such as his flying stunts in Godzilla vs. the Smog Monster and Godzilla vs. Gigan), they could just as often be wry and charming. Ever since Godzilla 1985, though, the first film in the Heisei series, filmmakers have been loathe to incorporate any of those elements of Godzilla’s earlier personality. In each of the subsequent movies (with the notable exception of Godzilla’s “origin story,” Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah, when the proto-Godzilla shows empathy for a group of trapped Japanese soldiers in World War Two), the Big G is portrayed as an angry dinosaur of very little brain, a virtually mindless engine of destruction (and thus a reflection of his persona in his very first appearance on the big screen).

Ten years after Toho relaunched their Godzilla character with Godzilla 1985, the first film of the Heisei series, rival studio Daiei relaunched their own popular kaiju star, Gamera, in his own Heisei series with Gamera: Guardian of the Universe (1995). (Gamera, of course, had been a late response to Godzilla’s success of the 1950s and 1960s, first appearing in 1965, after Godzilla had already starred in five films.) Two more Gamera films followed. Then, in 2006, filmmakers decided to reboot Gamera’s continuity yet again in Gamera the Brave. This film begins with the original Gamera sacrificing himself in 1973 to destroy several Gyaos monsters to save Earth. Thirty-three years later, a young boy discovers a glowing egg on an island, which hatches into a seemingly normal tortoise, but one which is actually the son of Gamera.

A Boy and His Turtle 1

The little tortoise soon alerts his owner, young Toru, that he is no ordinary turtle by levitating in the air. Soon thereafter, he begins a tremendous growth spurt, and the two friends are separated after the flying turtle, named Toto, outgrows Toru’s bedroom and Toru tries to find an outdoor home for his unusual pet. Later, Toru and Toto are reunited when a new, aggressive kaiju, Zedus, attacks Toru’s city. Toto’s initial effort to battle Zedus is unsuccessful, but Toru and the newly gigantic Toto team up to ultimately defeat the rampaging Zedus, and Toto takes up the full power set and mantle of his parent, Gamera.

A Boy and His Turtle 2

I’ll admit that Gamera the Brave ended up being a much more impressive and satisfying movie than I’d expected it to be. In large part, this is due to the strong performances given by the movie’s child actors (in stark contrast to the insufferable, grating, oftentimes almost unwatchable performances of child actors in the movies of the original Showa series; maybe it was the poor quality dubbing that made those performances seem so awful, but I can’t imagine the performances come off much better in the original Japanese). In comparing Gamera the Brave to Godzilla: Final Wars, I think the former film does a better job of encapsulating, modernizing, and strengthening the key element that gave the Showa films their appeal. The Gamera reboot tells the story of a powerful friendship between a child and a giant monster; beyond the original Gamera the Invincible (1965), all of the Showa series movies centered around Gamera’s efforts to befriend and protect the children of Japan. In contrast, Godzilla: Final Wars, while reintroducing a small army of Godzilla’s former allies and foes, ignores the relationships between the kaiju that provided so much of the appeal of the latter Showa series Godzilla films.

Unfortunately, Frank Darabont, screenwriter for the upcoming American Godzilla reboot, sounds determined to continue in the footsteps of his predecessor screenwriters of the Heisei and Millennium series Godzilla films, explaining in an interview that he wants his Godzilla to be perceived as a terrifying force of nature. He dismisses the later films of the Showa series:

“And then he became Clifford the Big Red Dog in the subsequent films. He became the mascot of Japan, he became the protector of Japan. Another big ugly monster would show up and he would fight that monster to protect Japan. Which I never really quite understood, the shift. What we’re trying to do with the new movie is not have it camp, not have it be campy. We’re kind of taking a cool new look at it.”

So Darabont seems to believe that the most recent Godzilla movie that Toho released was 1975’s Terror of Mechagodzilla. He acts as though the Heisei and Millennium films never existed, because what he describes is exactly how the makers of those films reconceptualized Godzilla, returning him to his original persona.

I don’t think this bodes well for an ongoing series of American Godzilla pictures. The last several Millennium series movies were disappointments at the box office (which is why Toho has taken a ten-year break from making any new Godzilla movies and has now licensed that responsibility to Legendary Pictures). It’s hard to sustain a series focused on a brainless “terrifying force of nature.”

At long last, the Big G gets his own star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame

But even if the newest Godzilla does a colossal belly flop in the theaters in 2014, at least the Big G can rest easy that he has his official star on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame, a gift from Hollywood on his fiftieth birthday…

Like this:

Like Loading...