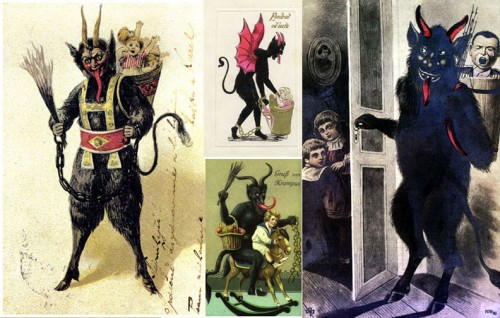

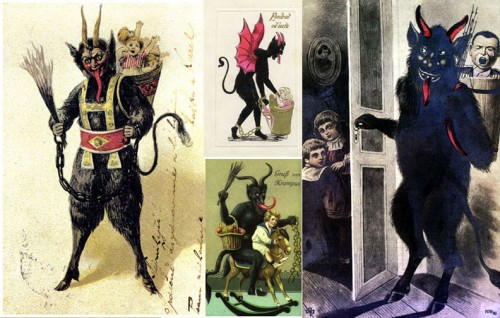

images of Krampus, bad luck spirit

Friday the Thirteenth feels like a very appropriate date on which to write a blog post about a book called The Bad Luck Spirits’ Social Aid and Pleasure Club. It also happens to be the day on which I’ve finished my fourth rewrite of my most ambitious, troublesome, labor-intensive, and longest-worked-on manuscript of any I’ve ever started.

Way back around the time I first started participating in George Alec Effinger’s writing workshop in New Orleans, sometime in 1995, mystery novelist Laura Joh Rowland, who had just published Shinju, the first novel in what is now a long-running series, talked some about the virtues of rigorously outlining a novel prior to starting it versus writing it as it goes, or “winging it.” She said the most difficult and tedious work she had ever had to do on a book was restructuring a failed novel, one which had not been successfully plotted out prior to its composition. All of the rework and the insertion of new scenes and the subtraction of unhelpful scenes, the deletion and/or addition of characters, and the spreading around of exposition were far more laborious and time-consuming, she said, than taking the time to carefully plot the book beforehand and then sticking mostly to the plan.

My first published novel, Fat White Vampire Blues, actually grew out of a novelette (which I later broke out into the first three chapters of the book). When I decided to expand it to novel length, I knew what my ending would be, but I pretty much filled in the middle parts as I went along. I got lucky; the book didn’t turn out overly long, and it didn’t crash and burn. Its sequel, Bride of the Fat White Vampire, has thus far been the only novel I’ve written under contract – meaning I had a firm deadline from my editor. Since I intended to structure it as a mystery novel, with lots of intricate turns of plot, I changed my methods and utilized a very detailed outline. The outline also allowed me to write the book, which turned out to be 20,000 words longer than the first one, in about half the time, eighteen months versus nearly three years. The method I used when writing my next book, The Good Humor Man, or, Calorie 3501, was somewhere between those I had used for the first two books. I thoroughly outlined the first half of the book, then winged it with the last half, expanding my outline as new ideas occurred to me.

Then came Hurricane Katrina, which turned more than a million persons’ lives upside down, mine included. My family and I ended up far luckier than many of our Gulf Coast neighbors. We didn’t lose our home (which “only” suffered about $18,000 worth of damage), and we didn’t end up trapped in the bureaucratic hell of the Road Home program. But we were stranded away from our house for two months, only finding housing and other necessities through the extraordinary kindness of friends and some relatives, and my wife Dara ended up losing her job when her agency was forced by the collapse of the New Orleans health care network to relocate to north Alabama. Plus, we had two babies (later three) to raise in a city where the future of most basic services, including health care, education, infrastructure maintenance, and public safety, was very much up in the air.

While Dara, Levi, Asher and I were stranded in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where we’d gone to attend the Bubonicon science fiction convention the weekend Katrina roared out of the Gulf, we had little to do aside from obsessively follow the news from New Orleans on CNN and the website of The Times-Picayune. One aspect of the coverage that simply floored me was how the news from my home town got worse and worse each day I watched. Just when I thought matters had gotten as dire as they possibly could, some new catastrophe would occur – snipers would fire rifles at helicopters attempting to rescue critically ill patients from the roof of the flooded Baptist Memorial Hospital, say, driving the helicopters off (a story which later came into dispute, but which was repeated endlessly on CNN and had an enormously demoralizing effect on those of us watching). The thought occurred to me that the evolving carnival of misery, destruction, death, and pervasive ineptness was simply beyond the scope of human foul-ups – so many things were going so incredibly wrong at so many levels that there simply had to be more to it than poor planning, poor execution, and political rivalries flaring at the most importune time.

That was how things looked in late August, September, and October of 2005. It wasn’t until a good bit later that I learned that a few agencies, including the U.S. Coast Guard and the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, had worked a succession of miracles rescuing people trapped by the floods, keeping the death toll far lower than that which had been forecast, and the disaster relief and rebuilding efforts provided by the non-profit sector and thousands of volunteers were models of efficaciousness and compassion. These were not the stories the major media outlets chose to cover during those early months.

It took a long time for a more balanced picture of the nation’s and the city’s response to Katrina to come into focus. In the meantime, living through the disaster’s aftermath, seeking to put our lives in New Orleans back together as best we could, I remained haunted by the intimation that something “extra” had been at work during the disaster. I certainly wasn’t alone in this. Conspiracy theories were rife in New Orleans and the various communities of storm exiles during the fall and winter of 2005, stories that shadowy forces had dynamited the flood control levees in the Lower Ninth Ward to prevent other, wealthier and whiter neighborhoods from flooding (didn’t work too well, considering the fate of Lakeview, one of the whitest neighborhoods in the city), or that President Bush had purposefully kneecapped the response efforts due to an animus against black people and/or the heavily Democratic city of New Orleans.

Being a fantasy/horror/science fiction writer, it was natural that my intimations should’ve led to an idea for a novel. The notion behind The Bad Luck Spirits’ Social Aid and Pleasure Club was fairly simple – the Katrina disaster had been made magnitudes worse by a conspiracy of supernatural bad luck entities who had worked diligently over many decades to hobble the health and resiliency of New Orleans and to drive its mortal residents away. My first literary reaction to the disaster and its aftermath had been to start a nonfiction book called The Janus-Faced City, an impressionistic history of the various political, economic , social, educational, and flood protection missteps which had accumulated in the decades leading to Katrina and had helped to ensure that the hurricane’s glancing blow would be horribly amplified. My hopes for obtaining a contract for that book sank when my agent, Dan Hooker, died of cancer on Thanksgiving of 2005.

Rather than continuing to crawl down what I feared would be a rabbit hole (I had never published a nonfiction book before, and I was suddenly without active representation), I redirected the fruits of my research into what I intended to be an epic contemporary fantasy novel. I wanted to write a fantastical secret history of the Katrina disaster, dramatizing the actual events of the catastrophe and also drawing away the curtain to show the various hobgoblins and tricksters and Evil Eye spirits pulling the strings of the mortal leaders and decision-makers. In January, 2006, I began writing notes and assembling an outline for a novel bigger and more ambitious than any I’d previously attempted.

In hindsight, I made several decisions at the outset that doomed me to write a very, very long book. Secret histories, by their very nature, tend to be lengthy enterprises. This is because the author has taken it upon himself to tell two narratives at once – a procession of actual, historical events, with their cast of real-life actors, and a shadow narrative of previously “unknown” occurrences which happen off-stage or hidden behind the scenery and which determine or significantly influence the “public” events of common knowledge. Tim Powers did a magnificent job of telling the secret history of the Cold War and the fall of the Soviet Union in Declare. Declare, however, in its dual tellings of actual twentieth century European history and the secret efforts of the British and Russian secret services to acquire the services of djinns, was a very long book. Not that this was a bad thing – I had thoroughly enjoyed Declare and its amazing cleverness several years prior to starting work on Bad Luck Spirits, and the novel had been a best seller for Tim Powers.

Also, the way I structured the Miasma Club, the bad luck spirits of the book’s title, had a major impact on the manuscript’s length. I wanted all of the major ethnic communities which had populated New Orleans to have a “representative” in the Miasma Club. An organization of bad luck spirits should have thirteen members, I figured. So I did my research and found thirteen (actually fourteen, counting both Na Ba and Na Ong, who are spouses and function as a team) trickster or Evil Eye spirits from the folklores of twelve ethnic or national groups which had populated New Orleans, starting with the Houma Indians and extending to the Vietnamese immigrants who had arrived in the wake of the end of the Vietnam War; I threw in Glenn the Gremlin as well, who didn’t represent an ethnic community but rather the community of engineers and scientists who had moved to New Orleans to work on the Apollo and space shuttle programs.

My bad luck spirits needed opponents, and the Muses of Greek mythology have a long history in New Orleans, their names adorning streets and Carnival krewes, so I included the Muses in my cast of characters. There are nine Muses. So, even before including a single mortal character, I found myself with a cast of twenty-three supernatural folks. One problem of assembling such a large cast is that you find yourself wanting, if not needing, to give each one something significant to do. My ambition was to reveal the entire post-Civil War history of New Orleans as a result of the ongoing conflict between the Miasma Club and the Muses, as well as the Miasma Club’s various schemes to bedevil the mortal citizenry. I decided to have my bad luck spirits specialize, each concentrating on causing maximum havoc and disruption among members of their own ethnic communities; and since members of those ethnic communities tended to favor certain occupations (the Irish going into law enforcement, for example), I also had the bad luck spirits specializing in degrading particular sectors of the local economy or political/social system. Not a bad choice on my part, certainly defensible given my ambitions for the book. But, again, this was a driver of complexity and thus of length.

Yet another decision I made contributed to expanding my manuscripts’ length well beyond the optimal. I wanted to focus on two main protagonists: Kay Rosenblatt, the Ashkenazic Jewish bad luck spirit, and Roy Rio, the black mayor of New Orleans, whom I intended to pattern upon the real mayor, Ray Nagin. That way, I could show both sides of the story, the mortal/”real life” side and the supernatural side. I decided to choose Kay as my supernatural protagonist because the story of Katrina’s Jewish survivors was very interesting to me and hadn’t received much attention. With two protagonists, I knew I had to entwine their stories at some point. But doing so was less than straightforward, since, not being an African-American bad luck spirit, Kay could not directly influence or bedevil Mayor Rio. So I found myself needing to connect them through relationships they would have in common, which meant introducing still more characters, the Weintraub family, whose ranks included love interests for both Kay and Mayor Rio. Again, by itself, nothing wrong with that choice. But added in with the other choices I had already made, I was cooking up a very, very big narrative.

I worked on my first draft from January, 2006 to November, 2008, nearly three years. The initial length? A modest, tidy 238,000 words.

A number of external players had changed during the nearly three years I’d spent writing my first draft. The publishing industry was one of them. The industry had lost a good bit of its self-confidence in that span. When my first two books had come out, in 2003 and 2004, long novels had been in vogue. Fat White Vampire Blues had been 135,000 words. Bride of the Fat White Vampire had been 155,000 words, and my editor at Random House hadn’t batted an eye regarding length. But by the end of 2008, with the start of the recession and following several years of hard economic times for publishers, most editors were now demanding novels closer to 100,000 words, books which would be cheaper to ship to stores and which stores could fit more copies of on their shelves and end-caps and display tables. Clearly, in that environment, 238,000 words was a non-starter.

Also, the man I’d patterned one of my two protagonists on, Mayor Ray Nagin, had changed. Mayor Nagin had come into office in 2002 as a reformer, a former businessman who promised to run city government efficiently and honestly. He became a local folk hero and somewhat of a national celebrity when, in the immediate aftermath of the levees bursting, eighty percent of the city flooding, and FEMA nowhere to be seen, he engaged in a profanity-laced meltdown on a national radio program and demanded the federal government to step up to the plate. However, in following months, perhaps worn down by the seemingly insuperable demands of the reconstruction, his political persona changed. He engaged in racially charged, divisive rhetoric, especially during the run-up to his reelection campaign, when he ran against a white candidate, Mitch Landrieu (who eventually replaced Nagin as mayor in 2010). His once sterling reputation for integrity was besmirched as one after another of his cronies and relatives were discovered to have benefitted from reconstruction projects. Civic-minded New Orleanians began yearning for the day he would leave office.

So I discovered the danger of writing a novel based on events which were still in play. My hero was based on Mayor Nagin, who was no longer acting in an admirable fashion; in fact, I found him to be increasingly contemptible as the months passed. Either I could stick with the Nagin portrayal and make my character, Roy Rio, a scoundrel, rather than a flawed but essentially admirable man, or I could sever the direct connection between Roy Rio and Ray Nagin and preserve the former as a sympathetic character.

I opted for the latter option. I also spent several months cutting 49,000 words from the manuscript, bringing it down to 189,000 words. My second agent had been attempting to market the novel as a partial (first three chapters and a synopsis). Finally I was able to give her the full manuscript to read. She balked at even the reduced length, saying we’d do much better in the marketplace if I could get the book down closer to 150,000 words. I said I was game to do another editing pass, but I was fresh out of ideas of what to cut. I asked for her advice. She began reading the manuscript, but I don’t believe she ever read it all the way through; she got hung up on one character she absolutely hated, a secondary character, Mayor Rio’s ex-wife, Councilwoman Cynthia Belvedere Hotchkiss. No matter how often I begged for her to read the entire book so she could give me educated feedback on what best to cut, I could not convince her to finish it. I never did receive any usable feedback on editing the book from her, and this ended up being a factor in my decision to seek different representation.

I mentioned my frustrations to my friend, the prolific and award-winning writer, Barry Malzberg. Barry, being both a prince and an incredibly quick reader, offered to read over my manuscript and give me his suggestions. Amazingly, he got back to me in less than a week after receiving the manuscript. He thought it needed to be shortened by at least another 40,000 words, that I should reduce a lot of the clutter and side-action, and that Mayor Rio’s character and motivations needed to be strengthened. He said I didn’t need to do anything different with Kay, as she already came through as a well-drawn, strongly motivated heroine.

I knew the only way I could cut another 40,000 words and strengthen Mayor Rio’s motivations at the same time would be to abandon in large part my ambition to make the novel a secret history of the Katrina disaster. I would need to have my disaster diverge from the disaster which had actually taken place. I had already done this to a minor extent, giving my storm a different name than Katrina and having it strike the Gulf Coast earlier in the season than Katrina did, figuring I would differentiate my plot just enough that I wouldn’t be held strictly accountable by readers to follow the exact timeline and events of the historical disaster. Now I saw myself pushing much farther away from my original intention, retaining only Katrina’s “greatest hits” in my plot.

By January of 2010, I had succeeded in cutting the book by another 38,000 words, down to 151,000 words. I had also moved on to other projects and was seeking new representation for them. When I signed with my current agent in the fall of 2010, my first order of business was to have him review and suggest improvements to Ghostlands, and later to The End of Daze. A year later, I asked if he would take a look at the most recent version of Bad Luck Spirits. I asked him for advice regarding whether I should self-publish the novel, perhaps broken into two e-books, or whether he would want to try marketing the shortened, improved version to a traditional publisher.

He told me he thought it was a good book and would be willing to put some effort into marketing it, should I be willing to implement his suggestions. He wanted me to ditch both prologues, each of dealt with the involvement of the miasmatic field with the early explorers and builders of the New Orleans region. He wanted me to squeeze as much as I could out of the first third of the book, the portion which takes place prior to the hurricane’s arrival. He told me that Kay is a stronger character than Roy Rio, and that I should refocus the book more on her story, less on his. He also wanted me to get rid of as much of the secondary viewpoints as I could, those chapters or portions of chapters told from the vantage points of bad luck spirits other than Kay.

Although I initially balked at getting rid of both prologues, I came to see the wisdom of his suggestions and followed them as best I could, without removing materials which are necessary to set up plot developments in the second half of the book and at its climax. The version I completed earlier today is 134,000 words, down an additional 17,000 words from the prior version.

So, as things now stand, The Bad Luck Spirits’ Social Aid and Pleasure Club is about the same length as Fat White Vampire Blues. I am a little stunned that I’ve been able to cut a total of 104,000 words between the initial version and this one, the fourth. Those 104,000 words exceed the lengths of my novels The Good Humor Man, or, Calorie 3501 and The End of Daze and nearly equal the length of my most recent book, No Direction Home. I must say that the effort of cutting those 104,000 words exceeded the effort of writing an equivalent number of words in either of the two latter books.

Contrary to what Laura Joh Rowland had warned against back in 1995, my error was not a failure to plan and outline my novel. I did plenty of planning and outlining before writing a single word of the manuscript. My errors were (1) adding too many characters; (2) trying to write the secret history of an event which was still unfolding at the time; (3) not properly gauging from my bloated outline how lengthy the book would initially be; and, perhaps most understandably, since few have correctly foretold the evolution of the publishing industry, (4) failing to predict that a much less welcoming market for long, complicated books would await me upon the manuscript’s completion.

Have I learned anything useful from this six-year-long experience? I certainly hope so. I spent longer working on this manuscript from beginning to end than I did on my bachelors and masters degrees combined.

And now, soon, it will be back out into the marketplace, whether I end up selling this book to a traditional publisher or going the do-it-yourself route. Please wish me luck. Just not bad luck… I’ve had enough of that with this manuscript already!

Like this:

Like Loading...