By pure happenstance, the last two books I read were both bildungsromans, novels of growing up, published within a quarter century of one another, with some marked similarities. Each was published to some acclaim, their authors being held in high regard by contemporary critics; yet the passage of time has proven far kinder to one book (and its author) than to the other. One of the books has never been out of print, is hailed as a masterpiece of twentieth century American literature, and continues to be widely read. The other has been reprinted only sporadically, most recently by a tiny university press, is noted (if at all) as a possible inspiration for a far more famous and influential media property, and its author is mostly forgotten, even in the genre of literature (speculative fiction) within which he published his most famous works. I approached the two novels with vastly different expectations. One, the one I had expected to love, was a partial disappointment, at times a taxing and tiresome read. The other, the one I had anticipated skimming mostly for historical and anthropological interest, turned out to be an unexpectedly moving and rewarding reading experience.

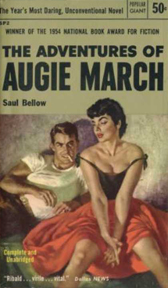

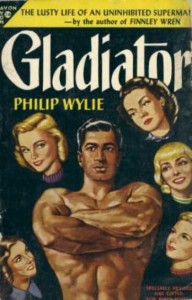

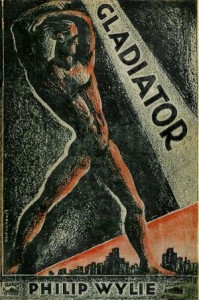

The two books are Saul Bellow’s The Adventures of Augie March (1953) and Philip Wylie’s Gladiator (1930). It is possible these particular two books have never been compared to one another before. I just performed a Google search; apart from my own blog post of earlier this week, I didn’t come across a single website or article that so much as mentions both books in the same context. I would guess most critics and literary reviewers would scoff at the notion of even mentioning the two books in the same breath. One is considered “serious literature” and the other “genre fiction” or “popular entertainment.” Augie March was awarded the National Book Award and is considered a masterpiece of one of America’s most highly regarded writers. Gladiator is remembered only by science fiction and superhero comic book buffs, and only by tiny minorities of those two communities. Yet I would propose, after having read the book, that Philip Wylie’s intentions in the areas of philosophical questioning and the exploration of how a character matures under duress were no less lofty than those of Saul Bellow twenty-three years later. Gladiator was not originally published as a serial in a pulp magazine or a dime novel; it was published by Alfred Knopf, and at the time of its publication, Philip Wylie was acquiring a reputation as an American H. G. Wells, a writer who combined serious social extrapolation with his fiction.

The similarities between the two novels’ protagonists and storylines are numerous. Both Augie March and Hugo Danner come from poor or lower middle class backgrounds in the Midwest or West (Augie from Chicago, Hugo from small town Colorado). Both characters are set apart from their peers by an innate peculiarity; for Hugo, it is his super-human strength and invulnerability, and for Augie, an unwillingness to apply himself to any particular goal, combined with a chameleon-like surface affability that causes more purposeful characters to continually pull Augie into their schemes. Both are bright and introspective, and both are given to warmth towards others. Both young men are powerfully attracted to college life, but neither succeeds at fitting into the college milieu. Both experience a long series of odd jobs and are faced with periods of hunger and physical deprivation, which alternate with episodes of improved fortune and relative luxury. Both join the Merchant Marine. Both Hugo and Augie are sucked by enthusiasm and events into war, Hugo into the First World War and Augie into the Second World War. Both are unsuccessful in love and experience a series of disappointing romances. Both occasionally run afoul of the law. Both come close to becoming involved with the Communist Party but ultimately avoid that fate. And both spend significant times of their young lives in rural Mexico.

That’s a long list of superficial similarities. Yet one book is universally considered “literature,” and the other is typically relegated to some stratum of “sub-literature.” Why? I’ve read them both, back to back, and I would not make that distinction between these two particular books. The literary critic D. G. Myers has wrestled with the notion of what constitutes literature, and this is what he has to say: “Literature is simply good writing—where ‘good’ has, by definition, no fixed definition.” He is saying that ‘good,’ if it has no fixed definition, is a subjective determination of value that varies from reader to reader. So what is my definition of a ‘good’ book? I’ve been a voracious reader much of my life. I have read books which have delighted me and stayed with me, and I have abandoned other books thirty pages in because I decided they were not worth my expenditure of time. I can list a number of qualities or “effects” which, if a book possesses them or elicits enough of those effects in me, lead me to place that book on my list of “good books.” They are:

Does the book delight me? Delight may include (1) surprising me with unexpected turns of events (but not events which defy established logics of the book’s characters or world); (2) providing me with a sense of aesthetic pleasure through skillful and evocative use of language; (3) introducing me to intriguing new (to me) places, new periods of history, or new activities, or portraying places, times, or activities with which I’m already familiar in a way new and illuminating to me; (4) making me laugh; (5) providing me with a sense of satisfaction or gratifying completion by following a pattern or structure which becomes apparent to me once I have finished reading the book, allowing me a thrill of recognition of at least some of the author’s intent; or (6) provides me with a sense of companionship from having spent time with a protagonist who strikes me as believable, well fleshed-out, and possessing interesting thoughts, observations, and opinions.

Does the book sustain my interest all the way through? Or does it bore or fatigue me? Do I comfortably remain within the “soap bubble” of the book’s imagined world, or do I find myself easily distracted and pulled away from the story and the prose?

Does the book arouse my emotions? Do I feel a sense of empathy for the protagonist and other characters?

Do parts of the book linger with me after I’ve finished reading it? Do I find myself reflecting back on a character’s dilemma or experience? Do any images which the book induced in my imagination recur in my imagination after that first impression? Do I continue hearing a character’s distinctive voice? Do I seek out memories of the book and replay them in my mind, rolling their flavors again over my tongue, because they are pleasurable?

Do I have any desire to reread the book at some time in the future?

Did I feel less alone while reading the book? Did the book allow me to feel less a “separate self,” cut off from the inner lives of other people?

While in the midst of reading the book, was I eager to pick it up again?

Would I be eager to recommend the book to friends?

Those are my criteria, my personal, subjective criteria, for judging the “goodness” of a book. So, taking these criteria into account, how do Gladiator and The Adventures of Augie March stack up against one another? I judge that each book scores points in different categories, and each holds distinct advantages over the other.

Gladiator was better at holding my attention all the way through than Augie March was. Hugo Danner’s central dilemma is simply more interesting and compelling than Augie March’s is. Hugo is a man born with the strength and resistance to hurt and harm that many of us fantasize about, and he is a man who wishes only to do well and right in the world, but who is stymied again and again by the limitations of his own imagination and the emotional shortcomings of those around him. Yet he continues to struggle against what seems a punishing Fate, thus earning in the reader’s mind the appellation “gladiator.” Augie is a smart and talented young man who is unable to settle on any particular goal and who ends up allowing people around him to draw him into their own designs and schemes, to Augie’s frequent disappointment. As a reader, I kept wanting to reach into the book and shake Augie’s shoulders and tell him, “Decide all ready! Make up your mind! Settle on a goal and apply yourself!”

Augie March provided me with more instances of delight than Gladiator did, but also far more instances of boredom, frustration, and temptation to set the book aside and start something else. Augie’s world teems with individually fascinating, grotesque, or bizarre minor characters, but at times this becomes a suffocating avalanche of riches. Particularly in the book’s first sixty pages, when Augie is still a child, we are introduced to one thoroughly fleshed-out minor character after another, many of them Dickensian in their individuality and strangeness, and the cumulative effect, for me, at least, was a sense of, “Why should I care about all these obnoxious, argumentative, and sometimes loathsome people?” Some of them go on to play major roles in the novel. Some do not. But I nearly bailed out on the book after fifty pages, particularly since Augie, its protagonist, was so undefined at that point and so overshadowed by this mass of unsympathetic minor characters. On average, the minor characters in Gladiator are much more flat and ill-defined than the minor characters in Augie March. Not all of them, but some; Hugo’s friends at college are little more than stock characterizations, quickly sketched, for example, as are the Communist Party organizer and archeologist depicted near the novel’s end, but the women Hugo becomes romantically involved with have inner lives to which we are given access, as do his father and his closest friend in the French Foreign Legion. Hugo lives in a less rich, abundant world of humanity than Augie does, but the minor characters in Hugo’s world don’t threaten to derail the novel’s plot or choke the reader with their superabundance, either.

Saul Bellow

Now that I have a little distance from both books, I find myself feeling closer to Augie than to Hugo. Augie’s voice remains with me more than Hugo’s does. This may be due, in part, to having experienced Augie’s first-person narration of his story for nearly six hundred pages, as opposed to experiencing Hugo’s story in third-person narration throughout a book less than half as long. But in great part this is due to one of Saul Bellow’s greatest strengths as a writer, his ability to create a very distinctive and memorable voice for his protagonists. Augie lingers with me due to his voice, his affability, his eagerness for love and openness to new experiences, his generosity in refraining from harsh judgements of his family, friends, and lovers, even when they’ve earned harsh judgement, and his self-deprecating sense of humor. He is a man I wouldn’t mind knowing personally, a man I could see easily befriending. On the other hand, he can be very tiresome, too. Oftentimes in the novel he is like one of those inebriated friends you found yourself sitting next to at a party in college, going on, and on, and on about various pet theories and philosophical notions. At some point, you want to say, “Go home, Augie! Get yourself to bed and sleep it off! I just can’t listen anymore!”

What were the high points of The Adventures of Augie March for me? As a reader, I wouldn’t change a thing about the entire sequence that takes place in Mexico — the eagle training, the assorted expatriots, and Augie’s ill-fated romance. It captivated me and will likely stick with me as one of my brightest memories of reading. Nearly as memorable and good were the “fish out of water” scenes of Augie being taken under the wings of various wealthy benefactors, his adult interactions with his older brother, the scenes of him making a precarious living by stealing textbooks, and the scenes of him floating in a lifeboat with an overly garrulous fellow survivor after his freighter is torpedoed by a U-boat.

Philip Wylie

What about the high points of

Gladiator? The sequence of scenes of Hugo fighting on the Western Front in France during the First World War are, in my mind, the heart of the book. At last, he finds himself in an environment where he doesn’t need to hide his strength, where he can push himself to the utmost of his abilities in pursuit of what he considers a noble goal, the victory of the Allied Powers. We readers all expect Hugo’s tremendous strength and ability to withstand machine gun fire to prove decisive. We’re rooting for him. But we are then confronted with the shocking irony that the war is too big, too destructive, too senseless for even Hugo to make more than a ripple in its ocean. As I stated in

my earlier essay on Gladiator, “even a man who can kill a thousand enemies in a single night is overshadowed by a war in which a single battle could result in half a million casualties.” Hugo’s commanders, while appreciative of his prowess, are too shortsighted, too unimaginative, and too stuck in conventional lines of military thinking to use him for much more than scouting or preventing their own trenches from being overrun. After Hugo’s best friend is killed by a German artillery shell and Hugo loses control of himself, wading into the German trenches and killing thousands of soldiers with his bare hands, he finds himself unable to exploit the momentary hole he has made in the German lines because he has reached the limits of his stamina and must retreat to his own trenches in order to eat and sleep. By the time he finally decides to go AWOL and attempt a scheme to end the war on his own by stealing an airplane, flying into Germany, and personally killing the German political leadership in Berlin, the Armistice is announced. The war ends without his having made an appreciable difference in it. The super-man might as well never have been a soldier at all.

Also very good are the scenes of Hugo attempting to earn money for college as a sideshow strongman in the midway at Coney Island. Philip Wylie paints these scenes and the characters Hugo interacts with there with nearly as deft a touch and an eye for telling detail as Saul Bellow exhibits in his portrayal of Augie’s Chicago. Much less effective, however, are Gladiator‘s final sequences, from the death of Hugo’s father on. I got the impression that Wylie must’ve written the last parts of the book in a rush to make a deadline, because the scenes of Hugo in Washington, DC and in Mexico feel flat and lifeless, almost cartoonish. The Adventures of Augie March does not end on a particularly strong note, either. I came to the final page and felt as if Bellow had simply said, “Enough!”

Which book would I be more eager to reread or to recommend to a friend? If I could have a greatly pruned The Adventures of Augie March, sort of a Portable Augie March, I would happily dive into it again and would enthusiastically recommend it to my friends. As the book stands, however, I could only recommend it with qualifications, and if I were to pick it up again, I would skip hundreds of its pages and run to the book’s central pleasure, the scenes in Mexico. I could read Gladiator again, but with less pleasure than I would take from rereading the Mexico portions of Augie March. Gladiator is a more consistent read, overall, than Augie March is, and I would judge it to be a better structured book. But I would also judge the high points of Augie March to soar higher than the high points of Gladiator.

So, of these two bildungsromans which I read back to back, which one would I say is the better book? After a good deal of consideration, I’d have to pick The Adventures of Augie March. But Augie wins on points, not by a knockout. So as a fight official, my score card is vastly different, I would imagine, from those of most critics, who would declare that these two novels don’t even belong in the same weight class or the same ring and would declare a mismatch. I don’t agree. “Let ’em fight!” I say.

Addendum: Looks like I misinterpreted D. G. Myers’ remarks above. He wrote to let me know that, contrary to my statement, “(Myers) is saying that ‘good,’ if it has no fixed definition, is a subjective determination of value that varies from reader to reader,” he does in fact believe literary value is objective and extrinsic, as he explains in this blog post.

My apologies to Professor Myers for any misunderstanding.

Like this:

Like Loading...