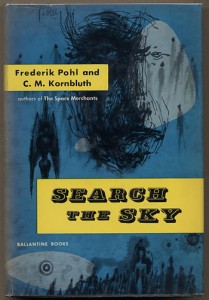

The Space Merchants

Frederik Pohl and C. M. Kornbluth

First published in serial form as Gravy Planet in Galaxy Science Fiction, 1952

Original book publication (simultaneous hardback and paperback): Ballantine Books, 1953

Most recent publication: (paperback) St. Martin’s Press, 2011

***********************************************

(return to Part 1: Introduction)

According to Frederik Pohl, one of the most significant literary collaborations in the history of the science fiction field got its start due to deadline pressure.

Pohl had started writing a mainstream novel about the advertising business while serving in the U.S. Army during World War Two, but he abandoned the project when he realized he really didn’t know anything about his subject. Following the war, he set out to rectify this. He worked for several years as a copywriter for the small advertising firm of Twing and Altman, mainly working book accounts. He ended up with a good bit of insider knowledge about the advertising business, but author Fred Wakeman had just published a novel called The Hucksters about advertising, so Pohl felt the idea of a story about the advertising business was no longer fresh; at least not as a mainstream novel. But as a science fiction novel…? That field was yet unplowed.

He spent a year or two writing the first 20,000 words, then showed what he had written to Horace Gold, editor of Galaxy Science Fiction. Gold had just finished serializing Alfred Bester’s The Demolished Man and was anxious for another high profile serial to follow it up with. He wanted to publish the first 20,000 words of Pohl’s novel immediately, in the upcoming issue of Galaxy – on the stipulation that Pohl could turn in the second and third installments of the novel in a week’s time.

Pohl was stuck, however. He didn’t know where to take the book’s plot next. Desperate to finish the novel within the very tight deadline he’d been given, he turned to his close friend, Cyril Kornbluth, who was then staying with the Pohls at their home in Red Bank, New Jersey. Kornbluth offered to help. They ended up working their collaboration on The Space Merchants (first titled Gravy Planet for the novel’s serialization in Galaxy, and expanded the following year for book publication by Ballantine) in a different fashion from the method they worked out for later shared works. Kornbluth read over the first 20,000 words and made some revisions. Then he wrote the middle third of the book on his own, which was in turn revised by Pohl. The two writers alternated four-page bursts of the last third. They made their deadline. (Pohl related the story in his introduction to His Share of Glory: the Complete Short Science Fiction of C. M. Kornbluth.)

The future society which Pohl designed and which Kornbluth helped to flesh out is a sort of inverse of fascism. In the fascism of Italy under Mussolini and Germany under Hitler, authoritarian central governments allowed private industry and commerce to continue, but placed their direction under state control. In the future society of The Space Merchants, government has been colonized and is being completely controlled by commercial interests, the most powerful of which are the giant advertising agencies. Things have reached the point where, rather than being identified as, say, the representative from North Dakota, an elected official is referred to as the representative from Fowler Shocken, the powerful ad firm which employs the novel’s protagonist, Mitch Courtenay, a “Copysmith Star-Class.” In this vastly overpopulated future society (where members of the middle class sleep in stairwells of the giant office towers in which they work and the most powerful and wealthy executives can afford only a two-room apartment; in this, The Space Merchants was a precursor of Harry Harrison’s Make Room! Make Room!), the population is divided into executives, producers, and consumers, and the advertising agencies teach the vast majority of the swollen population from birth to dying day to be happy with their role as consumers. Virtually every bit of the Earth’s surface is devoted to either production or consumption, even the polar regions, which play host to resort and amusement areas where constricted populaces can briefly enjoy comparatively endless vistas out on the frozen tundra. This society does have its rebels, a secret society of saboteurs and terrorists called the Consies, or Conservationists. Named, of course, to remind readers of the Commies (the book was written in 1952), the Consies are remarkably predictive of the radical elements of the contemporary worldwide Green movement.

At the book’s outset, Mitch Courtenay is handed management of his company’s biggest and newest account — convincing thousands of Americans to become colonists on Venus, a harsh, forbidding world, which may remain an exceedingly inhospitable planet for human beings for generations, until planetary geo-engineering manages to transform Venus into something more akin to Earth. Only one man has previously set down on Venus and returned to Earth safely, a midget astronaut named Jack O’Shea. Pohl utilized his experience in the advertising business to great effect in his depiction of the early interactions between O’Shea and Courtenay, who has been assigned the task of extracting from the astronaut any useful information about the environment of Venus; useful for selling the desirability of serving as a colonist, that is. For Courtenay is selling “space” in two senses of the word — the excitement and romance of”outer space,” and the possibility for ordinary citizens to acquire “living space” far in excess of anything known by even the wealthiest men in America. In exchange for selling Venus to potential colonists, the firm of Fowler Shocken is promised all of the mineral and raw materials rights of Venus. Other ad firms also covet those rights, and they are willing to go to extreme measures to acquire them. Courtenay is opposed in his work by agents and saboteurs both from a rival ad agency, Taunton Associates, and the Consies. And he finds that these agents and saboteurs may include his friends, coworkers, and possibly even his wife.

Keen observers of science fiction recognized the significance of The Space Merchants almost immediately. The New York Times upon the book’s initial publication, at a time when major newspapers virtually never paid attention to science fiction, praised the two writers for their “slide rule precision” in their creation of a plausible future society and called the book “a novel of the future that the present must inevitably rank as a classic.” British novelist and critic Kingsley Amis devoted nine pages of his pioneering work of SF criticism from 1960, New Maps of Hell, to The Space Merchants, saying the book “has many claims to being the best science fiction novel so far.” Amis writes:

“The Space Merchants, clearly, is an admonitory satire on certain aspects of our own society, mainly economic, but it is not only that. It does not simply show the already impending consequences of the growth of industrial and commercial power, and it does more than simply satirize or criticize existing habits in the advertising profession… Beyond all this, the book seems to be interested in the future as such, to inquire what might result from turns of events that are possible and are not invalidated by being unlikely, to confront men and women with a thing, as I put it, which may put them into a situation without precedence in our experience.”

Of particular relevance to the subject of my essay, which is an attempted disaggregation of the Pohl-Kornbluth partnership and the strengths contributed by both, Amis has this to say:

“I will leave to the L. Sprague de Camps of the future the final determination of which partner is responsible for which scenes, but a check of Kornbluth’s individual work — Not This August, in which America retrieves a total defeat by Russia and China, or [The] Syndic, a chronicle of minor wars following upon a major one — soon suggests that his part in The Space Merchants was roughly to provide the more violent action while Pohl filled in the social background and the satire. … The closing scenes, on which I suspect the hand of Kornbluth lies heavily, offer little but adequate excitement and are not altogether a conclusion to the issues raised in the opening chapters. To provide a solution to these is not what would be expected from Pohl, who like the best of his colleagues is far more concerned to state, with as much elaboration as possible, ‘the case against tomorrow’ than to suggest any straightforward mitigations. … Even The Space Merchants relies, as it goes on, more and more heavily upon Kornbluthian elements — there is a quite gratuitous scene with a female sadistic maniac who totes a sharpened knitting needle.”

Although I agree with Amis that The Space Merchants ranks high in the pantheon of significant SF works, I strongly disagree with him on his evaluation of what he terms the book’s “Kornbluthian elements.” A tremendous admirer of Frederik Pohl, he sought to downgrade Kornbluth’s contribution to the book to mere word padding and mixing in some thrills for the cheap seats (an assessment I’m sure Fred Pohl would be the first to disagree with). It seems clear, both from Amis’s judgement of what Cyril Kornbluth contributed to the partnership and the critic’s citing of Kornbluth’s novel-length works only, that Amis was unfamiliar with Kornbluth’s short fiction, where his writerly skills and his outlook on the world can be viewed in their clearest light. “The Little Black Bag,” perhaps Kornbluth’s finest story, is filled with wonderful prose, rich in felt physical detail and penetrating characterization. Its ending is the kind of ineluctable and entirely fitting horror to be found in the best of Poe. To judge from much of his best short fiction, including “The Marching Morons,” “The Silly Season,” and “The Luckiest Man in Denv,” Kornbluth did not have a very high regard for the morality and worthiness of his fellow human beings. His outlook could be described as misanthropic, but it was also very, very sharp and funny. For example, whether or not Kornbluth was indeed responsible for the scene late in The Space Merchants involving the woman sadist who tortures Mitchell Courtenay — and I believe it was likely this was a Kornbluth contribution (a number of his solo works feature scheming or malevolent women) — I disagree that the scene was gratuitous and added only for shock value. The scene and the warped character of Hedy both have a point to make (pun only partly intended). Taunton’s use of Hedy illustrates the advertising mogul’s ruthlessness. Also, in the world of The Space Merchants, men and women have become so trained to adhere to the pleasure principle by the world’s advertising agencies that Copysmith Star-Class Mitchell Courtenay reflects that murderers, assassins, and torturers have virtually disappeared, due to fear of punishment. Yet Taunton reminds him, just before deploying Hedy, that humanity has always contained rare individuals who actually seek out pain and punishment, and that with the enormously inflated population of the book’s future society, such extreme masochists are much more common than they once were. Such seekers of punishment are the deadly tools the advertising agencies utilize in their low-level wars with their rival agencies.

Also, I have the benefit of Pohl’s recollections of how he and Kornbluth tackled the writing of The Space Merchants, which were not available to Kingsley Amis in 1960. According to Pohl, he was primarily responsible for the book’s first third, and Kornbluth was primarily responsible for the middle third, with the final third having been split between them in small work increments of four or five pages. With this knowledge, we can perhaps better separate out what each man brought to the novel.

The book’s first third belongs primarily to Frederik Pohl. In it, he delineated the outlines of his future society, its economy, its politics, and its major social problems (according to him, working out all the details of the book’s first third took between one and two years, a very extended period of development for an otherwise quick writer; in contrast, the two collaborators finished the second two thirds of the novel in one week!). Pohl’s skills of social and economic extrapolation, also seen in his short works of the period, such as “The Midas Plague,” really shine in this section. He also makes very effective use of his insider knowledge of the advertising business, seasoning his descriptions of the Fowler Shocken Agency with telling bits of dialogue between coworkers, the rituals of advertising campaign proposals, and office infighting and politics. Some of his portrayals, particularly of the agency’s “yes men,” are overly broad, bordering on stock types and caricatures, but they work well in context. Interestingly, and not common for SF works of the period, the protagonist, Michael Courtenay, and his wife Kathy (apparently they are in the midst of a trial marriage, because Michael begs her to make it permanent at the end of the trial period in a few months), are shown to be in an unstable, tempestuous relationship, on the brink of foundering. I’m not sure whether this is a detail Pohl contributed, or an element which Kornbluth introduced in his revision of the first third. The reason I suspect it might be Kornbluth’s doing is that Kornbluth featured unhappy or rocky romances and marriages in many of his solo stories and longer works.

Pohl wrote this about his friend Cyril Kornbluth in his introduction to The Best of C. M. Kornbluth:

“[Cyril] was also a sardonic soul. The comedy present in almost everything he wrote relates to the essential hypocricies and foolishnesses of mankind. His target was not always Man in the abstract and general. Sometimes it was one particular man, or woman, thinly disguised as a character in a story — and thinly sliced, into quivering bits. Once or twice it was me.”

Kornbluth was primarily responsible for the book’s middle third. This is the section of the novel, I’ll admit, that I found the most enjoyable and entertaining. In The Way the Future Was, Fred Pohl relates that at some point when he was struggling to come up with a way to continue the book beyond its initial twenty thousand words, Phil Klass (who wrote under the pen name William Tenn) suggested that one way to go might be to have Michael Courtenay lose his privileged position as a Star-Class Copysmith and experience the world from the vantage point of a lower class producer and consumer. Fred liked the idea, and when Cyril Kornbluth offered to help with finishing the book, Fred suggested Phil Klass’s idea, and Kornbluth liked it, as well. So Michael finds himself shanghaied by an untrustworthy coworker and dumped into steerage on a tramp freighter bringing menial workers to a gigantic food processing plant in Costa Rica, his identity erased and replaced by that of a peon virtually without rights of any kind. From the comparative lap of luxury, Michael is thrust into the lower depths; the reader can tell that Kornbluth had tremendous fun with this set-up, because the reader has tremendous fun along with him. The Space Merchants is meant to be a satire, a comedy. I found the book’s funniest bit to be when Michael finds himself gradually succumbing to a circular, triple addiction designed by his own advertising agency to ensnare the consumer class. The harsh physical labor dehydrates Michael, and the only beverage of any kind available to quench his thirst is Popsie, an addictive soda. The soda makes him hungry, and the only snack available is Crunchies, which cause withdrawal symptoms that can only be quelled by more sips of Popsie. But drinking too much Popsie makes Michael crave Starr cigarettes, and smoking those makes it impossible for him not to eat more Crunchies… As comedy, it’s brilliant, and as a satire of Western consumer mores, it is biting and spot-on.

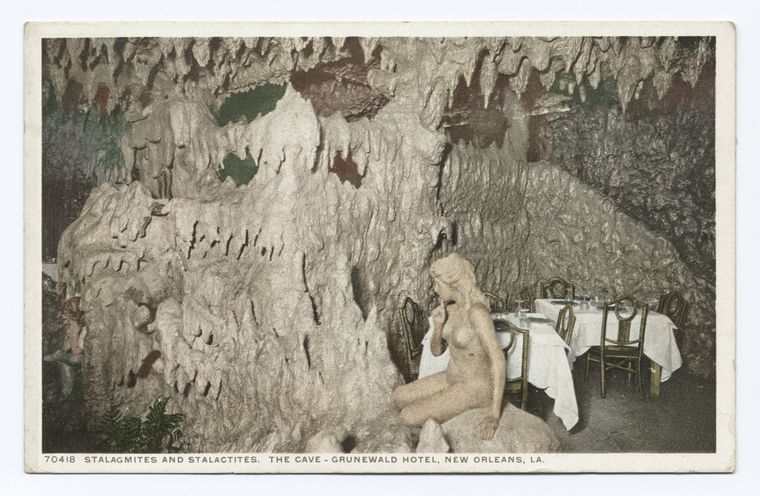

The work unit Michael finds himself shanghaied into is the United Slime-Mold Protein Workers of Panamerica, working for Chlorella Proteins, whose principal product is a kind of genetically engineered poultry. Michael is comically exploited by both the company and his union. Breakfast, lunch, and dinner consist primarily of slices of Chicken Little, the gigantic, headless, limbless chicken-thing that regrows its protein-saturated mass as quickly as workers of Chlorella Proteins can slice hunks of it off (Michael’s initial job is to harvest the slime molds which are utilized as Chicken Little’s feed stock). Around the book’s middle point, Kornbluth has Michael pretend to sign on with the secretive, underground Consies in order to gain a reassignment to New York City, so that he can reestablish his old identity and reclaim his place in his old advertising firm (where his bosses and most of his coworkers believe he is dead, killed in an accident at a resort at the South Pole). In one of the book’s strangest, most vividly described passages, Michael meets the Consies in their underground lair — the entrance to which is hidden beneath Chicken Little. The method with which Michael and his Consie handler make their way through Chicken Little to the hatchway is to utilize a hypersonic whistle, which, when blown, causes Chicken Little to involuntarily pull away from the vector in which the sound is directed. Thus, the two men travel through a “bubble” that moves through a hundred-ton mass of living protein… perhaps one of the weirdest images in the history of science fiction, and a minor triumph of Cyril Kornbluth’s fertile (and bizarre) imagination.

I found that the novel becomes somewhat less involving (and thrillingly strange) in its final third, when Michael returns to New York City. This is the third which Pohl and Kornbluth wrote together in alternating four-page sections (which Pohl then went back and revised). This is not to say that the book’s conclusion lacks its thrills and pleasures; the scenes set in the stairwells of the Taunton Associates Building are as strong as any earlier in the book. The Consies play an important role in the book’s climax. Interestingly, the environmental radicals are portrayed in a much different light within the novel’s final twenty pages than they were in the book’s middle third. Kornbluth portrayed the Consies as somewhat bumbling, rather comical extremists. Whoever wrote the novel’s last pages — and I suspect it was Pohl — showed the Consies to be mankind’s likeliest saviors, a secret alliance of the enlightened that would preserve a terraformed Venus as a pristine wilderness, one which can replace the Earth’s lost natural spaces, Terran wildernesses which were raped and processed out of existence by corporate entities such as Fowler Shocken. Frederik Pohl has always had an element of utopianism in his work. He vividly described the few years he spent in the late 1930s as a member of the Young Communist League in his memoir, The Way the Future Was. He abandoned the Communist Party after the Hitler-Stalin Pact, but he never abandoned his support for and belief in left-liberal causes. Cyril Kornbluth, however, to judge from his solo work, particularly his short fiction, was no believer in the gradual perfectability of human society. No utopian, he. He seemed to believe, rather, that men would always find a way to foul things up, no matter how advanced their technology might become.

This thematic tension between the collaborators, the tension between the optimistic utopian and the pessimistic misanthrope, is what gives The Space Merchants much of its zing and what sets it apart from nearly all of its contemporaries. It is a novel in argument with itself. This disagreement between the two writers’ outlooks is also a large part of what sets the three best collaborative novels of Frederik Pohl and Cyril Kornbluth shoulders above any of the solo novels either of them wrote during the 1950s. Kornbluth provided the ying to Pohl’s yang.

Next: Search the Sky

Like this:

Like Loading...