Some of Your Blood

by Theodore Sturgeon

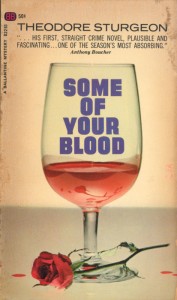

Original printing: Ballantine Mystery, paperback original, 1961

Most recent printing: Centipede Press, paperback, 2006

I do believe Theodore Sturgeon’s 1961 psychological suspense thriller Some of Your Blood wins the “Don’t Judge a Book By Its Cover” award, at least regarding its 1966 second paperback printing. I sought out this book because I had heard it referred to as “Ted Sturgeon’s offbeat vampire novel.” Well, anyone with any familiarity with the works of Theodore Sturgeon — with books such as The Dreaming Jewels and More Than Human or stories such as “Slow Sculpture” and “If All Men Were Brothers, Would You Let One Marry Your Sister?” or the classic Star Trek episode “Amok Time” – could tell you that “Ted Sturgeon’s offbeat vampire novel” could mean any of several hundred different story concepts. The man was that unpredictable and inventive a writer.

But the cover to that 1966 second printing sure did sucker me. A wine glass filled with either a blush red wine or blood; a single rose lying beneath the wine glass; drops of red liquid, either wine or blood again, bracketing the rose… what does such a cover image make you think of?

I’ll tell you what it makes me think of, particularly in the realm of “offbeat vampire novels” – I figured Ted Sturgeon would be riffing on the Bram Stoker image of the vampire as irresistible seducer, subverting that popular twentieth century notion of vampire as suave, romantic, savage lover/conqueror. I’d done it myself with my novel Fat White Vampire Blues, and I looked forward to seeing how a master storyteller like Ted Sturgeon would pull off a similar trick to what I had done.

Well, boy howdy, was I ever wrong!

And delighted to be wrong, as things turned out.

There are no supernatural elements in Some of Your Blood. Many critics and reviewers have classified it as a horror novel. Anthony Boucher, in his cover blurb to the 1966 reprinting, describes it as “… his (Sturgeon’s) first, straight crime novel.” Personally, I wouldn’t call it either a horror novel or a straight crime novel. Crimes are committed by the protagonist, and they are horrific; but I feel the label “psychological suspense thriller” applies most aptly. Feel free to slap your own favored label on the book. But by all means, read it, because it is a wonderful example of whatever it happens to be.

Many aficionados of Sturgeon’s body of work have noted that his prime subject matter is love. Certainly, if he can be said to be predictable in any way as a writer, he is predictably empathetic to all expressions of love and to their progenitors, no matter how perverse or far from the mainstream. Ted Sturgeon, in his stories and novels, never recoiled. He always embraced, no matter how sticky or icky that embrace might be, and he encouraged his readers to surrender with him to that embrace.

There are no despicable characters in Some of Your Blood. The closest any of the characters comes to despicableness is the protagonist’s brutal father, but, in true Sturgeon fashion, even he is allowed moments of humanity and shades of likability. The book has no villains; only victims of adverse environments. It features two Army doctors who struggle against harrowing Korean War-era resource limitations and bureaucratic resistance to do the right and proper thing by their charge and patient. Its protagonist is by turns clever, amoral, innocent, opaque, endearing, violent, infantile, volatile, and pathetic. But this reader, in the sure, steady hands of the author, stuck with the pseudonymous George Smith all the way through, never tempted to turn away in disgust or to reject the character as a monster beyond the pale.

I would like to have been the proverbial “fly on the wall” of a typical reader’s bedroom back in 1961, when the novel first appeared. The book’s key revelations would have seemed much more shocking and much less expected, I’m certain, than they do for a typical reader in 2012, fifty-one years later. Even so, our present time’s greater familiarity and degree of comfort with outliers on the range of psycho-sexual behaviors, with what used to be universally thought of as perversions, do not appreciably decrease the novel’s power and impact. If the book is less shocking today, it is all the more engaging as a character study and a sympathetic, in-depth visit with a damaged psyche.

I won’t spoil it for you. I won’t tell you what “George Smith” does or why he does it. Read the book. You’ll be doing yourself a favor.