Every now and then, one snaps to the realization that several of one’s pursuits or activities, due to no conscious design, fit together like the gears of a nice pocket watch. It happened to me this past weekend – a sort of “satori for geeks.”

Ever since this past summer, when I was finally able to divorce myself from my habit (of five year’s duration) of easing my three boys into sleep by lying down in bed with them (often falling asleep myself), and thus reclaimed some nightly reading time, I’ve been pursuing the project of reading much of the notable classic science fiction that I somehow missed out on during my personal Golden Age of Science Fiction (my teen years). Two of the writers whose vintage paperbacks have been falling into my acquisitive fingers with increasing frequency have been Philip Jose Farmer and Michael Moorcock. As a teen, I’m pretty sure all I read of Farmer was his collection Strange Relations, and my familiarity with Moorcock was limited to his novel-length version of Behold the Man (I wasn’t into sword and sorcery, so I avoided his then-omnipresent Elric books, and his Jerry Cornelius books weren’t widely available when I would’ve been apt to pick them up in the late 1970s or early 1980s).

I’ve been collecting the “frisky Farmer” books, his early forays into exploring human-alien sex and the like. So far, I’ve found copies of The Lovers (the 1961 novelization of his 1953 short story), Dare, and Flesh, plus several of his Tarzan pastiches, which I’m sure have various forms of sex or sex-play in them. When it comes to old paperbacks, I prefer to find them in my local used bookstores or at conventions, but I think I may break down and utilize the Internets to get my hands on his two “pornographic” SF novels of the 1960s, Image of the Beast and Blown (which have been published by at least two publishers as a combined edition).

Michael Moorcock has also been popping up on my radar screen. I chanced into a nice vintage hardback copy of the second of his Jerry Cornelius novels from the late 1960s, A Cure for Cancer. I already had his collection of Jerry Cornelius short fiction, The Life and Times of Jerry Cornelius, sitting on my shelf waiting to be read, and, being a completest (and also having this blog to somehow fill each week), I have set off on a quest (also likely to be cut short by a visit to the Internets) for the other three Jerry Cornelius novels (which have been published both as stand-alones and as omnibus editions).

I also bought books two and four of his Jherek Carnelian/Dancers at the End of Time series, The Hollow Lands and The Transformation of Miss Mavis Ming, which means, of course, that my next order of business must be acquiring books one and three, An Alien Heat and The End of All Songs (which, like the Cornelius books, are available in several different handy omnibus editions). Jerry Cornelius and Jherek Carnelian are both avatars of Moorcock’s Eternal Champion, Cornelius being the 1960s embodiment (along with Elric, of course) and Carnelian being the 1970s embodiment (or one of them, Moorcock having been incredibly prolific throughout the 1960s and 1970s, sometimes writing books at a rate of 15,000 words per day, cranking them out in three or four days apiece!).

Accompanying my book-buying binges are occasional jazz CD buying binges. My most recent purchase was a meaty, satisfying compilation from Blue Note Records, Artist Selects: Lou Donaldson, in which the alto saxophonist picked out thirteen of his favorite tracks from his more than two decades of putting out albums on the Blue Note label. The earliest selections on the CD date from the early 1950s, when Lou sat in on a number of hard bop sessions with drummer/band leader Art Blakey and introduced pianist Horace Silver and trumpeter Clifford Brown to the Blue Note stable. Most of the second half of the cuts on the CD come from Lou’s “soul jazz” period, which began with his classic album Blues Walk in 1958. One of the keys to the Lou Donaldson quintet’s unique sound was the inclusion of conga drummer Ray Barretto, which made his numbers danceable, and which secured him placement in jukeboxes around the country. Not long after Blues Walk, Lou settled on a standard format for his soul jazz records, groups that included electric organ and guitar players (he liked having an organist accompany him because an electric organ was easy to transport, and many of the small clubs Lou’s groups played didn’t own a piano). This remained his preferred format throughout the 1960s. His most popular album of that time was Alligator Boogaloo, recorded in 1967, featuring Melvin Lastie on cornet, Lonnie Smith on organ, George Benson (before he became a singing star) on guitar, and the talented New Orleanian Leo Morris on drums. The title cut originated as a throwaway piece, an elaboration on a vamping groove that Lou conjured up at the last minute to fill four empty minutes on the record, but it ended up being the most commercially successful piece he ever recorded.

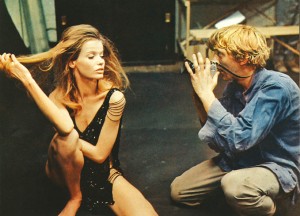

What brought these disparate works of pop culture together for me in flash of “geek satori?” It was watching Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1966 film Blow-Up on Turner Classic Movies. The Italian director’s first film in English (he made two more, Zabriskie Point and The Passenger, the latter starring Jack Nicholson), it was set in the Swinging London of the mid-1960s and featured a protagonist loosely based on a real-life British fashion photographer of the period. This movie, just like the only other Antonioni film I’ve seen, the earlier The Red Desert, is a visual feast, with stunning, unforgettable cinematography. It’s also a marvelous period piece, capturing the mod Swinging London of the Sixties like a fly trapped in shimmering celluloid amber. David Hemmings, who plays the unnamed photographer, lives in a sprawling photographer’s commune in an industrial part of London and drives an enormous Bentley convertible with blaise abandon, weaving it through streets meant for cars half its size. His days are filled with sexually provocative fashion shoots and the would-be groupies his notoriety attracts, and his evenings are filled with parties he experiences through a haze of drugs and alcohol. The City of London is rife with protesters against nuclear war and racism, as well as an “action squad” of mimes who drive about in an Army-surplus truck, looking for an audience.

The film’s plot (such as it is) hinges on a chance encounter between the photographer and two lovers in a neighborhood park. The photographer shoots a series of photos of the couple from long range, before being spotted by the woman (Vanessa Redgrave), who is considerably younger than her apparent paramour. She tracks the photographer back to his studio/commune and demands that he turn over his negatives. Intrigued by her reactions, he gives her a roll of film, but substitutes a different set of photos. Later, when he develops the photos of the couple, he sees, hidden in the bushes behind them, what might be a man with a gun and a dead body. He blows the images up in an attempt to figure out if what he thinks he sees was actually there. That evening, he returns to the park and finds the dead body. However, he has forgotten to bring his camera along. He goes to a party where he knows his agent will be present, intending to recruit him to return with him to the park to view the body. But he gets sidetracked by all of the drugs and sex available at the gathering. When he awakens the next morning and returns home, he discovers that, in his absence, all of the photos of the couple, plus his negatives, have been removed from his studio, which has been thoroughly ransacked. That evening, he spots the character portrayed by Vanessa Redgrave outside a theater. He follows her inside, only to get sidetracked once again by the wild scene inside, a raucous concert given by the Yardbirds. He loses her. The film ends the following morning, when he returns to the park and finds the body gone, no evidence left behind of it ever having been there. When he walks out of the park, the mime “action squad” spots him and their truck pulls over. The mimes spill out of the truck and rush to the park’s tennis court, where two of them mime a tennis match while the rest of them watch the “game.” The photographer watches, too. One of the mimes pretends to hit the “ball” over the fence, then signals for the photographer to fetch it. He pretends to toss it back to them. In the film’s final shot, he begins hearing the sounds of a tennis match from the mimed game.

My take on the film is that it was a subtle but telling broadside against the excesses of its age. The photographer is bored and filled with ennui due to the emptiness of his life and his fixation upon vapid surfaces. When something real and important — a possible murder — intrudes upon his existence, he is drawn to it, yet he is unable to extract himself from the morass of his over-stimulated milieu to do anything about it, either alert the authorities or solve the mystery of the killing himself. When we last see him, he is ascribing reality — the sounds of a ball being struck by a tennis racket — to phenomena which do not exist, to a mimed fantasy.

How do my other current leisure-time obsessions fit in with Blow-Up? Part of the film’s affect of alienation is achieved by the lack, for much of the film, of a musical soundtrack. The only times music is heard in the film is when one of the characters turns on a radio or a phonograph player or attends a concert. One of the only occasions on which David Hemmings’ character expresses any enthusiasm is when he plays a jazz record for the Vanessa Redgrave character. Although all of the movie’s instrumental music was composed by jazz pianist Herbie Hancock, this bit of jazz sounds exactly like Lou Donaldson’s quintet from Alligator Boogaloo. Soul jazz was very popular in the Swinging London of the mid-1960s, particularly electric organ groups. Herbie Hancock played on a number of Blue Note albums with Lou Donaldson, so he was very familiar with that sound. The photographer’s ultra-alpha male persona with women, his easy domination of his models and groupies, so easy that he becomes bored with the ease of it, reminded me very strongly of the protagonist of Philip Jose Farmer’s 1960 novel Flesh, an astronaut who returns to Earth after an absence of eight hundred years, only to be turned into the Sunhero, a living sex totem surgically enhanced with “the pure sex power of fifty bulls” (to quote from the back cover copy from a late 1960s reprint edition). But most of all, watching Blow-Up made me eager to dive into Michael Moorcock’s Jerry Cornelius novels and stories. Cornelius sprang from the exact same milieu that produced the photographer of Blow-Up. Moorcock and his good friend J. G. Ballard were an integral part of the Swinging London scene, one of the few times when the worlds of science fiction and the art world’s avant garde intersected (the only other time I can think of would be the Weimar Germany of the 1920s, when science fiction films like Fritz Lang’s Metropolis showcased German Expressionism).

What can I say about my having the experience of watching one of the key cinematic portraits of Swinging London enhanced by my serendipitous choices in reading and listening material?

Absolutely fab.

Andrew,

I am compelled to point out a significant correction regarding the film Blow-Up. The rock band in the theatre scene is the British band, the (post-Clapton) Yardbirds, not the American band the Byrds. Definitely a great film, I first saw it in the early 70’s in a high school film class I took.

Stephen, thanks so much for making that catch, and thanks for visiting my site. I’ll make the correction (easy to see how I misremembered the Yardbirds as the Byrds). Come back and visit again.