I just finished reading Philip Wylie’s 1930 novel Gladiator. I’d heard about the book for years, both as one of the earliest speculative fiction novels on the subject of a super-human (appearing five years prior to Olaf Stapleton’s Odd John and ten years before A. E. van Vogt’s Slan was serialized in Astounding) and as the purported inspiration for the creation of Superman by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster in 1938.

On the surface, certain parallels between Hugo Danner, protagonist of Gladiator, and the original version of Superman are striking. Their power sets were virtually identical; Danner could run as fast as a locomotive, leap forty feet straight into the air or hurl a church steeple with a running start, lift up to five tons, and had skin impenetrable by anything short of an exploding artillery shell. Also, Danner spends part of the book attempting to root out corrupt politicians and industrialists from their center of power in Washington, DC, a pursuit echoed by a decidedly populist Superman in many pre-war issues of Action Comics and Superman (in Metropolis, rather than Washington). However, according to Gregory Feeley, who has looked into all the relevant sources, Gladiator may not have had anything to do with the inspiration for Superman. The novel initially found very few readers, selling less than 2,600 copies in its first hardcover printing from Alfred Knopf. During interviews they granted late in life, both Siegel and Shuster acknowledged several inspirations for their character, including the pulp action hero Doc Savage, but do not mention Wylie’s Gladiator. Sam Moskowitz’s claim of the link between the 1930 novel and the 1938 Action Comics character, published in his 1963 book of portraits of SF writers, Explorers of the Infinite, was based upon a single interview with Wylie. Gregory Feeley points out that the differences between Hugo Danner and Clark Kent/Superman are more notable, perhaps, than the similarities. Danner received his powers as the result of an experiment his chemist father carried out on Danner’s mother while she was pregnant, not as the result of coming from another planet; and Danner never puts on a costume, adopts a secret identity, or battles criminals as a vigilante, although following one of his frequent failures to achieve his ambitions, he fantasizes about doing the latter (or, alternatively, about becoming what we today would call a super-villain).

A friend of mine located for me a paperback reprint of the novel, published by the University of Nebraska’s Bison Press in 2004. Having just spent weeks laboring through Saul Bellow’s The Adventures of Augie March (more on that in my next post), I decided I needed a palate cleanser, something less challenging and a much quicker read. Gladiator seemed to fit the bill. I mainly picked up the book out of archeological interest, wanting to determine for myself any linkages between what I figured would be an antiquated, eighty year-old relic of the pulp era and the subsequent development of the super-hero in comics and films. What I discovered to my surprise was a novel centered on a sophisticated and sometimes subtle characterization of a believable, conflicted, and very three-dimensional protagonist, a book that could bear favorable comparisons, not only with its more renowned contemporaries like Odd John, but also with far more recent novels on similar themes, such as Robert Silverberg’s classic Dying Inside (1972).

As a reader in 2011 who has been marinated in forty years’ worth of super-hero comic books and films, I came to Gladiator with a considerably different set of preconceived notions and penumbras of earlier reading experiences than the novel’s original readers would have had back in 1930. I’ve had the benefit of having read Alan Moore’s Watchmen and Miracleman, Peter David’s Hulk, Mark Waid’s Kingdom Come, Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns, and Mark Gruenwald’s Squadron Supreme. A familiarity with these comics and graphic novels enormously enriches one’s experience of Gladiator, because one can easily see reflections of Hugo Danner’s travails in all of those later works, whether the influence was direct (as it possibly was in the case of Moore, who visually “quoted” Gladiator in Watchmen) or indirect.

To me, a far more interesting question than whether or not Jerry Siegel or Joe Shuster read Gladiator in the 1930s is if Stan Lee read Gladiator in the early 1960s. The novel’s portrait of a man more cursed than blessed by his super-human strength and abilities is strongly echoed by Lee’s characterizations of Spider-Man, the Hulk, and the Silver Surfer (and Lee’s pioneering work in the 1960s led to those deeper examinations of the dilemmas and conundrums of being super-human that I list above). Hugo Danner spends his entire adolescent and adult life searching for a purpose toward which to apply his enormous strength, and the varied purposes he pursues and ends up abandoning encompass almost the entire range of plots utilized by writers of super-hero stories since 1938. In order of attempt, Danner seeks personal glory through excelling at collegiate athletics; accumulation of wealth (or just making enough dough for a meal) through use of his physical strength; satisfaction through saving lives in danger; being able to “cut loose” during wartime and seek vengeance for the deaths of friends in battle; he tries to live up to a parental figure’s hopes; temporarily turns his back on his abilities in an effort to find normalcy and serenity; tries to root out corruption in government and the justice system; seeks to use his strength in the service of scientific exploration; and finally contemplates founding a utopia in the jungle and populating it with children having abilities like his. The tragedy of the novel — and it is a tragedy — is that Danner, despite his pure intentions, despite the rigid control he mostly maintains over his use of his abilities, either is foiled in each of these pursuits by the ignorance, fear, or venality of his fellow men, or he has rueful second thoughts about goals for which he was initially wild with enthusiasm, realizing that his dreams are unrealistic, given human nature. The book ends with Danner considering himself a failure, even though the reader will recognize that he has won many small victories throughout the novel, albeit victories on a far smaller scale than those for which Danner had yearned.

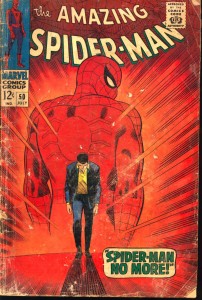

In many respects, Hugo Danner more closely resembles Peter Parker/Spider-Man than he does Clark Kent/Superman. Danner’s scientist father’s goal is to find a way to increase the efficiency of human muscle mass to that of the muscles of ants and grasshoppers, and he succeeds with his infant son (after first succeeding, far more horrifically, with a kitten he comes to name Samson). Danner ends up with the proportional strength of an ant and the proportional leaping ability and speed of a grasshopper, whereas Peter Parker ends up, far more famously, with the proportional strength and speed of a spider. The famous scene from Amazing Fantasy #15 and the first Spider-Man movie of Peter Parker, under an assumed identity, entering a ring with a professional wrestler in order to win a cash prize was foreshadowed decades earlier by an almost identical scene in Gladiator, wherein Hugo Danner uses a false name to win a hundred dollars by knocking out a professional boxer a foot taller and eighty pounds heavier than he is (in another Peter Parker-like touch, the reason Danner does this is to raise cash for a bus ticket back to Webster College after having been seduced, then robbed by a call girl in New York City). Danner’s foray into heroism and service to others, like Peter Parker’s, is preceded by a tragic death caused, in part, by a personal failing on the part of the protagonist. In Peter Parker’s case, his selfish refusal to interfere with a robber’s escape leads to the death of Peter’s Uncle Ben at the hands of that same robber. In Hugo Danner’s case, his anger on the football field at a personal snub from the jealous captain of his team leads Danner to momentarily let go of his self-control and hit an opposing player too hard in the process of scoring a touchdown, snapping the young man’s neck in three places. The big difference between the two characters? Peter Parker, meant almost from the start to be a character in a recurring series of stories, utilizes his shame and self-recrimination to forge a philosophy of “With great power comes great responsibility” and then embarks upon a career as Spider-Man which has now lasted nearly a half century. Hugo Danner, the protagonist of a single novel, struggles mightily to find a purpose for his power and never succeeds, or at least never manages to live up to the Olympian standard he sets for himself.

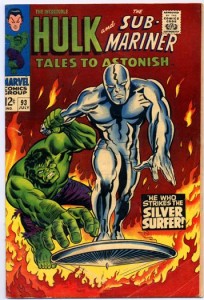

Danner also resembles another Stan Lee creation, the Incredible Hulk. Danner’s scientist father experiments on a pregnant cat before experimenting on his own wife. The result is a kitten with the strength of an ox. In a series of horrific scenes, among the most effective in the book, the super-kitten nearly destroys the Danners’ home and savagely kills several sheep and cattle. A farmer’s rifle bullet fails to kill it. Danner is forced to poison the creature when it returns to his house for a saucer of milk and a plate of meat. After this experience, Danner and his neurotically religious wife take special care to condition Hugo, once the baby shows signs of his super-human strength, against any expression of anger, use of violence, or open display of his prowess. They are mostly successful in this, although both as an infant and as a child, Hugo occasionally lets signs of his abnormality show, which results in his being ostracized by most of the other children in his town and by their parents. Throughout the book, Danner worries about his potential for losing control and struggles against incitements and temptations to give his anger (and his inhuman strength) free reign. His college career as a star football player is ended when Danner, goaded by a jealous teammate, momentarily forgets to self-limit himself to one-fifth of his abilities on the playing field and accidentally kills an opposing player. Danner’s potential as a killer is shown in full during his service with the French Foreign Legion during World War One, when, in the bloody aftermath of the death of his best friend from German artillery fire, Danner plows into the German trenches and kills a thousand soldiers with his bare hands. Another parallel with an early Hulk story (in this case, The Avengers #1)? Seeking refuge and peace, the Hulk “hides in open sight” by joining a circus and performing as a super-strong robot. In Danner’s case, when he suddenly learns that his parents will be unable to pay for his second year at Webster College, he raises money for his education by getting a job as a strong man on the Coney Island midway, trusting in audiences’ assumption of some form of fakery to mask the extent of his natural abilities.

Another theme of the novel is Danner’s continual search for acceptance, friendship, and love. The ordinary people who surround him can sense his difference, even when he is completely successful at hiding his abnormal strength. This sense of difference leads to distrust, fear, and often to hatred. Danner, after taking a job as a farm hand, finds love with the farmer’s neglected wife, only to see her love turn to horror after Danner is forced to kill a marauding bull by breaking its skull with his fist. In one key scene, Danner rescues a bank coworker who has become trapped in a bank vault and is close to suffocation. All conventional efforts to open the jammed vault have failed. Danner offers to rescue the man, but only if all other persons will leave the basement and will not inquire into his method. He then rips off the vault’s door with his bare hands. The bank’s president questions Danner, suspecting that he has devised a new method of safe cracking that he means to use criminally in the future. When Danner refuses to answer his boss’s questions, the executive has Danner arrested by a corrupt police chief, who then attempts to torture an answer out of Danner. Stan Lee utilized this pattern of a protagonist’s good deed leading to social condemnation and ostracism regularly, particularly in stories involving Spider-Man, the Hulk, the Sub-Mariner, or the Silver Surfer. Of all these, Hugo Danner is perhaps the most similar, personality-wise, to the Silver Surfer, one of Lee’s personal favorites. Both characters are portrayed as lonely introverts, frequently soliloquizing on the short-sighted foolishnesses of humanity, yet yearning all the same for human companionship and acceptance, trying to help those in need and sometimes succeeding, but never achieving any recognition. No issue of the classic Stan Lee-John Buscema run of The Silver Surfer was complete without the Surfer retreating to an isolated mountaintop and ruing his exile on Earth and the shortcomings of humanity. Gladiator ends the same way, with Hugo Danner on a mountaintop in Mexico, remonstrating with God.

As a reader conditioned by the “Dark and Gritty” era of super-hero storytelling that followed the publications of The Dark Knight Returns, Miracleman, and Watchmen in the mid-1980s, I kept waiting for Hugo Danner to truly lose it. In an early scene set during his time at Webster College, Danner gets drunk for the first time in his life, at a party attended by his fraternity brothers and a horde of showgirls. Intimations of Alan Moore’s Miracleman led me on, making me anticipate a horrific consequence on the scale of one of Young Nastyman’s drunken binges in the South Seas or Young Miracleman’s nihilistic destruction of part of London. But the worst that happens is that Danner goes home with one of the young women, passes out after having sex, and awakens the next morning with his wallet gone. Danner does let his anger and grief take over in 1918 in France after the Germans kill his best friend, but the Young Miracleman-like slaughter he inflicts on the German troops is camouflaged by the far more massive carnage taking place all along the Western Front; even a man who can kill a thousand enemies in a single night is overshadowed by a war in which a single battle could result in half a million casualties. In his civilian life back in America, the one time that Danner would have been fully justified in cutting loose and dismembering his foes, following his torture at the hands of corrupt police after he has freed a man trapped in a bank vault, he manages to retain control, limiting himself to an intimidating display of his abilities. I thought I might be disappointed by the author’s choice not to have his protagonist engage in vengeance which (most) modern super-characters would have allowed themselves. But Wylie is so successful in illuminating Hugo Danner’s character, his upbringing, and his sense of ethics that I fully “bought” Danner’s decision to be merciful, not feeling that it was a cop-out on the writer’s part.

Fans of the best work of Stan Lee, Alan Moore, Kurt Busiek, and Frank Miller exploring what it means to be super-human owe it to themselves to find a copy of Gladiator and read it, not as a historical curiosity, but as an engaging and enlightening novel. Philip Wylie covered their territory first, decades before most of them began their careers in comics. And he did so with a deftness, craftsmanship, and powers of extrapolation that make his book just as readable as it was upon its first publication in 1930. In fact, perhaps even a better fit for today’s comics-savvy audience than it was for those 2,568 readers who bought copies of the first edition from Alfred Knopf during the early years of the Great Depression.

Andy,

I enjoyed this essay a lot, as I always do your writing, no matter what the subject! You’re as readable as Charles Willeford, whose four Hoke Moseley books I’ve been re-reading, which I recommend, by the way, if you want to give yourself a vacation in another genre, a mystery detective series that’s funny and set in your Miami home in the 80’s and earlier. One of his characters mentioned mangoes the other day and I thought of you and how you detest this precious fruit because your youth reeked of it.

Anyway, the question I wanted to ask: Do you think that the misunderstood-by-society element of the modern superhero/monster characters might have originated with Mary Shelley’s _Frankenstein_? I remember how affecting that part of the novel was when I finally read it, and how unlike the movie monster the “monster” really was, the novel version being just a poor dumb creature trying to get along and do the right thing, ruined by his looks. (I can relate.) Do you know of even earlier uses of this theme than Shelley’s? Perhaps from Greek mythology, where the gods did play tricks?

Thanks,

Fritz

Hey, Fritz! Great to hear from you! Interesting that you should mention Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. If you go to the link I provide to Gregory Feeley’s essay on Gladiator, he compares Hugo Danner to Frankenstein’s creature. Off the top of my head, the only Greek myth I can think of that sort of utilizes the theme of tragic efforts at gift giving is the story of Prometheus the Titan, who offered fire to man and was then punished by the gods by being doomed to having his liver repeatedly eaten away by crows. The Titans were described as a race of giant monsters, but Prometheus seems to have had the interests of mankind more in his heart than the majority of the (more aesthetically correct) gods did.